Click image to open full size in new tab

Article Text

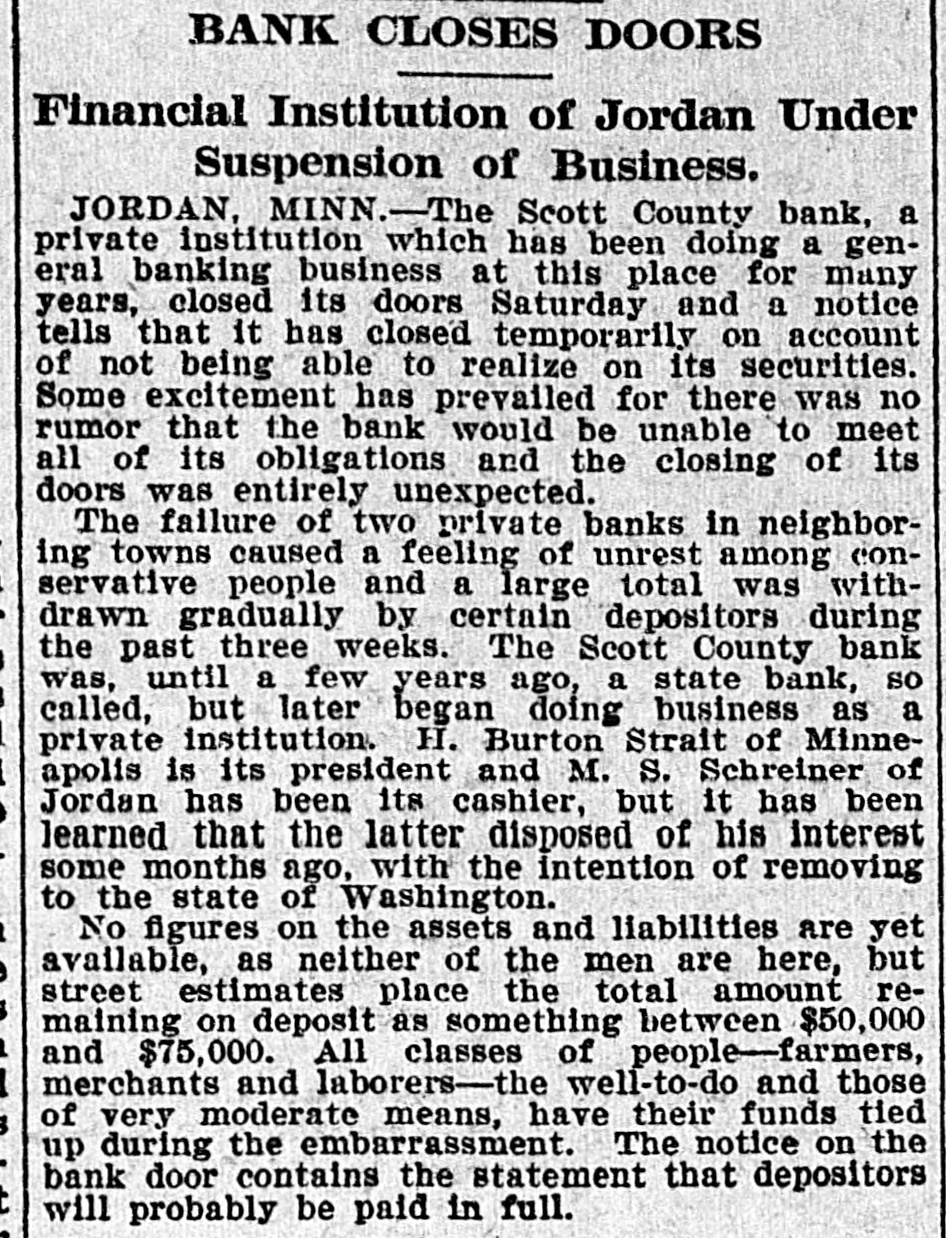

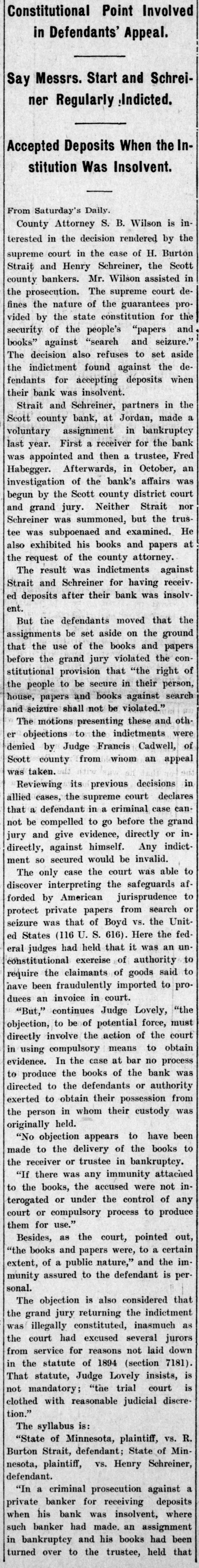

Constitutional Point Involved in Defendants' Appeal. Say Messrs. Start and Schreiner Regularly Indicted. Accepted Deposits When the Institution Was Insolvent. From Saturday's Daily. County Attorney S. B. Wilson is interested in the decision rendered by the supreme court in the case of H. Burton Strait and Henry Schreiner, the Scott county bankers. Mr. Wilson assisted in the prosecution. The supreme court defines the nature of the guarantees provided by the state constitution for the security of the people's "papers and books" against "search and seizure." The decision also refuses to set aside the indictment found against the defendants for accepting deposits when their bank was insolvent. Strait and Schreiner, partners in the Scott county bank, at Jordan, made a voluntary assignment in bankruptcy last year. First a receiver for the bank was appointed and then a trustee, Fred Habegger. Afterwards, in October, an investigation of the bank's affairs was begun by the Scott county district court and grand jury. Neither Strait nor Schreiner was summoned, but the trustee was subpoenaed and examined. He also exhibited his books and papers at the request of the county attorney. The result was indictments against Strait and Schreiner for having received deposits after their bank was insolvent. But the defendants moved that the assignments be set aside on the ground that the use of the books and papers before the grand jury violated the constitutional provision that "the right of the people to be secure in their person, house, papers and books against search and seizure shall not be violated." The motions presenting these and other objections to the indictments were denied by Judge Francis Cadwell, of Scott county from whom an appeal was taken. Reviewing its previous decisions in allied cases, the supreme court declares that a defendant in a criminal case cannot be compelled to go before the grand jury and give evidence, directly or indirectly, against himself. Any indictment so secured would be invalid. The only case the court was able to discover interpreting the safeguards afforded by American jurisprudence to protect private papers from search or seizure was that of Boyd vs. the United States (116 U. S. 616). Here the federal judges had held that it was an unconstitutional exercise of authority to require the claimants of goods said to have been fraudulently imported to produces an invoice in court. "But," continues Judge Lovely, "the objection, to be of potential force, must directly involve the action of the court in using compulsory means to obtain evidence. In the case at bar no process to produce the books of the bank was directed to the defendants or authority exerted to obtain their possession from the person in whom their custody was originally held. "No objection appears to have been made to the delivery of the books to the receiver or trustee in bankruptcy. "If there was any immunity attached to the books, the accused were not interogated or under the control of any court or compulsory process to produce them for use." Besides, as the court, pointed out, "the books and papers were, to a certain extent, of a public nature," and the immunity assured to the defendant is personal. The objection is also considered that the grand jury returning the indictment was illegally constituted, inasmuch as the court had excused several jurors from service for reasons not laid down in the statute of 1894 (section 7181). That statute, Judge Lovely insists, is not mandatory; "the trial court is clothed with reasonable judicial discretion." The syllabus is: "State of Minnesota, plaintiff, VS. R. Burton Strait defendant State of Min.