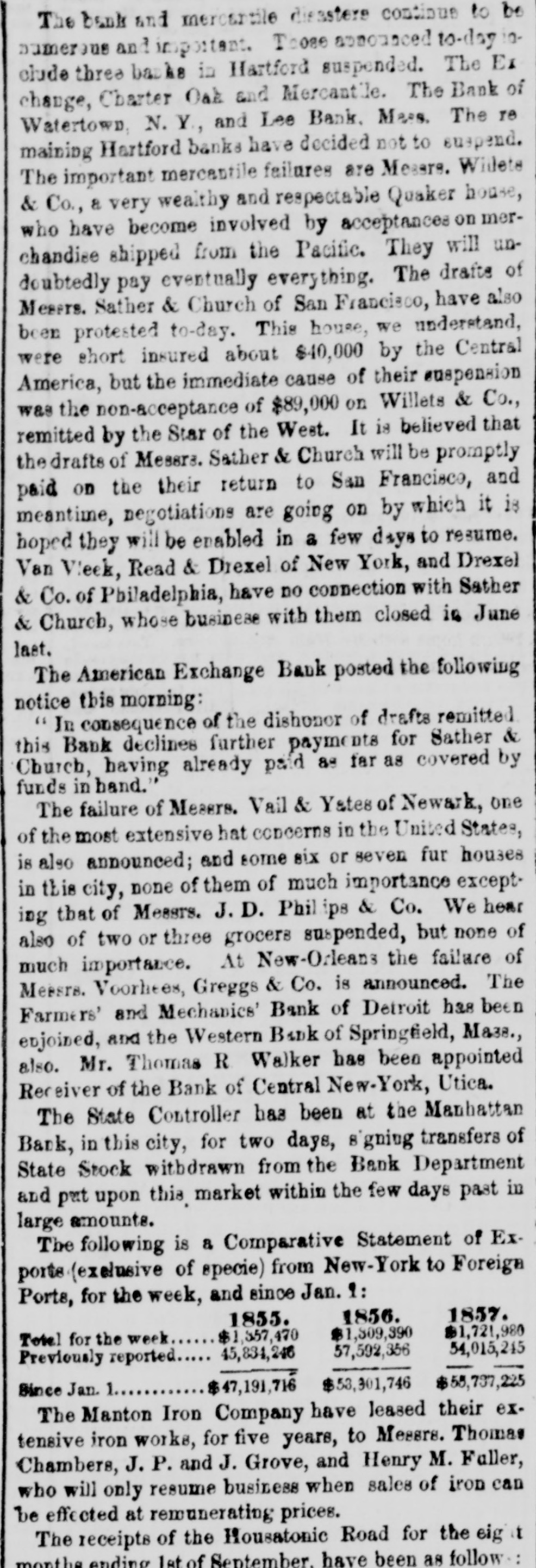

Article Text

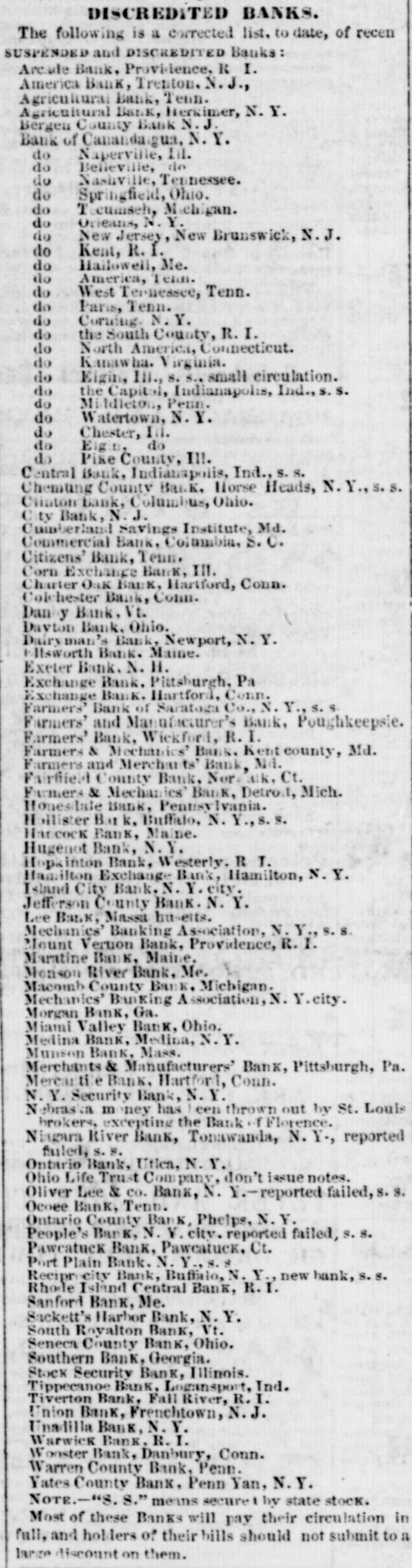

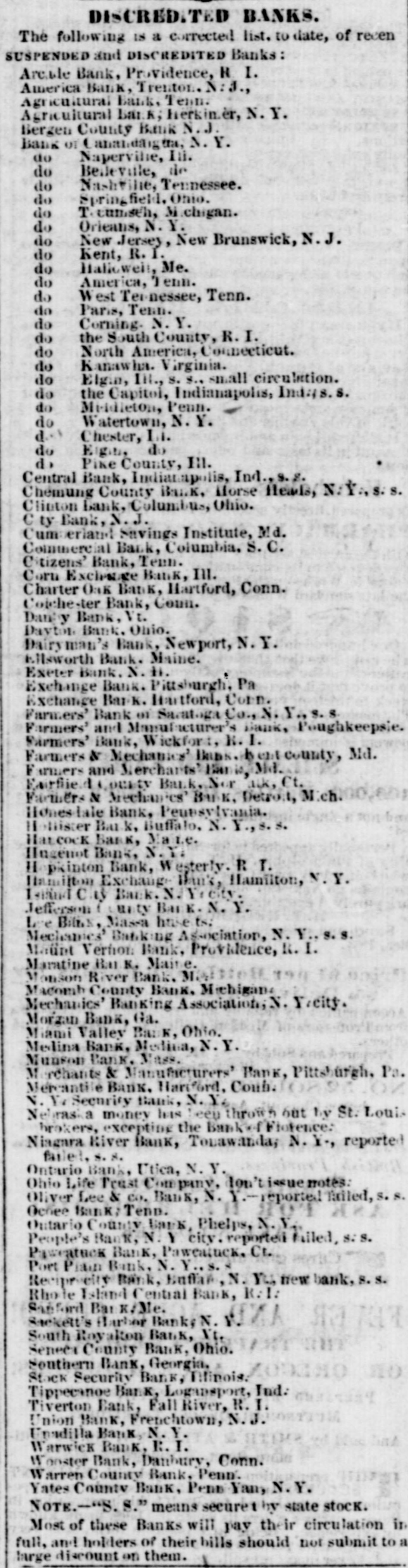

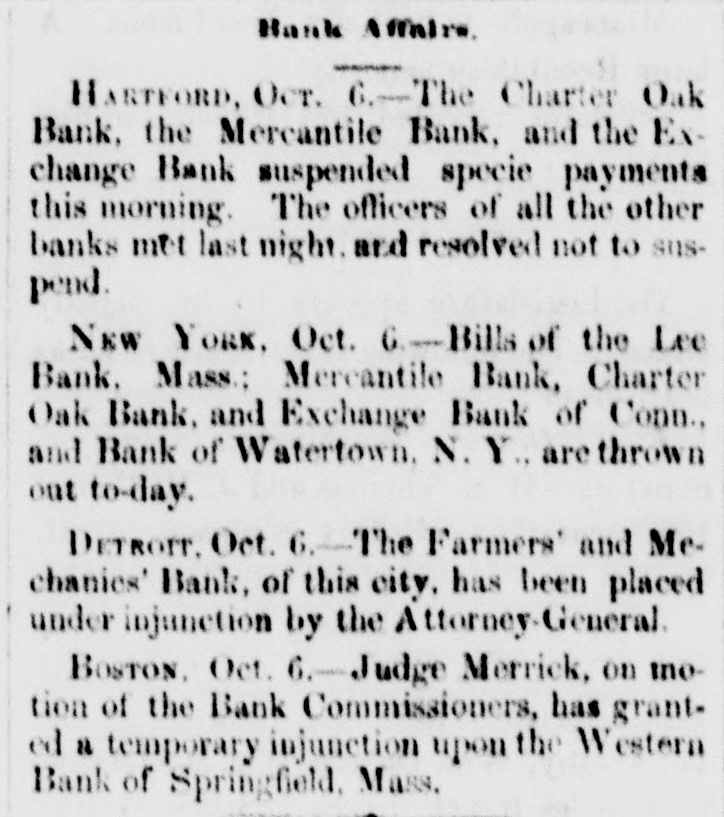

DISCREDITED BANKS. The following is a corrected list, to date, of recen SUSPENDED and DISCREDITED Banks: Arcade Bank, Providence, R I. America Bank, Trenton. N.J., Agricultural Bank, Tenn. Agricultural Bank, Herkimer, N. Y. Bergen County Bank N.J. Bank of Canandaigua, N. Y. do Naperville, III. do Believille, de do Nashville, Tennessee. do Springfield, Ohio. do Tecumsch, Michigan. do Orleans, N.Y. do New Jersey, New Brunswick, N.J. do Kent, R.I. do Hallowell, Me. do America, Tenn. do West Ternessee, Tenn. do Paris, Tenn. do Corning. N.Y. do the South County, R. I. do North America, Connecticut. do Kanawha. V Tirginia. do Eigin, III., S. S., small circulation. do the Capitol, Indianapolis, Ind., S. S. do Middleton, Penn. do Watertown, N.Y. do Chester, III. do Eigin, do do Pike County, III. Central Bank, Indianapolis, Ind., S.S. Chemting County Bank, Horse Heads, N.Y., S. S. Clinton bank, Columbus, Ohio. City Bank, N.J. Cumberland Savings Institute, Md. Commercial Bank, Columbia, S. C. Citizens' Bank, Tenn. Corn Exchange Bank, Ill. Charter Oak Bank, Hartford, Conn. Colchester Bank, Conn. Dan Bank, Vt. Dayton Bank. Ohio. Dairy Bank, Newport, N.Y. Ellsworth Bank. Maine. Exeter Bank. N. H. Exchange Bank, Pittsburgh, Pa Exchange Bank. Hartford, Conn. Farmers' Bank of Saratoga Co., N. Y.,s.s Farmers' and Manufacturer's Bank, Poughkeepsie. Farmers' Bank, Wickford, R.I. Farmers & Mechanics' Bank, Kent county, Md. Farmers and Merchants Bank, Md. Fairfield County Bank, Nor. alk, Ct. Farmers & Mechanics' Bank, Detroit, Mich. Honesitate Bank, Pennsylvania. Hollister Bar k, Buffalo, N. Y., S. Hancock Bank, Maine. Hugenot Bank, N.Y. Hopkinton Bank, Westerly. R T. Hamilton Exchange Bank, Hamilton, N.Y. Island City Bank, N. Y. city. Jefferson County Bank. N. Y. Lee Bank, Massa husetts. Mechanics' Banking Association, N. Y., S.S. Mount Vernon Bank, Providence, R. I. Maratine Bank, Maine. Monson River Bank, Me. Macomb County Bank, Michigan. Mechanics' Banking Association, N. Y.city. Morgan Bank, Ga. Miami Valley Bank, Ohio. Medina Bank, Medina, N.Y. Munson Bank, Mass. Merchants & Manufacturers' Bank, Pittsburgh, Pa. Mercar tile Bank, Hartford, Conn. N.Y. Security Bank, N.Y. Nebraska m ney has been thrown out by St. Louis brokers, excepting the Bank of Florence. Niagara River Bank, Tonawanda, N. Y., reported failed, S.S. Ontario Bank, Utica, N.Y. Ohio Life Trust Company, don't issue notes. Oliver Lee & co. Bank, N. Y.-reported failed, S. S. Ocoee Bank, Tenn. Ontario County Bank, Phelps, N.Y. People's Bank, N. V. city. reported failed, S. S. Pawcatuck Bank, Pawcatuck, Ct. Port Plain Bank. N. Y.,s.s Recipr city Bank, Buffalo, N. Y., new bank, S. S. Rhode Island Central Bank, R.I. Sanford Bank, Me. Sackett's Harbor Bank, N.Y. South Royalton Bank, Vt. Seneca County Bank, Ohio. Southern Bank, Georgia. Stock Security Bank, Illinois. Tippecanoe Bank, Logansport, Ind. Tiverton Bank, Fall River, R.I. Union Bank, Frenchtown, N.J. Unadilla Bank, N.Y. Warwick Bank, R. I. Wonster Bank, Danbury, Conn. Warren County Bank, Penn. Yates County Bank, Penn Yan, N.Y. NOTE.-"S. 8." means securet by state stock. Most of these Banks will pay their circulation in full, and holders of their bills should not submit to a large discount on them.