Click image to open full size in new tab

Article Text

The First National Bank was ready to do anything in its power-it only awaited a formal request. Other banks also expressed their friendliness.

One hundred and fifty thousand dollars of the borrowed money was to be delivered on Nov. 14. That morning President Coolbaugh was found dead at the foot of the Douglas monument with a bullet hole in his temple. His bank, fearing for its own safety, refused to advance the promised money. The First National Bank followed its example. New York long since had refused a friendly hand-and the Third National Bank found itself deeper than ever in the meshes of misfortune.

About this time the park commissioners discovered suddenly that there was a large block of bonds not yet due which they could pay. Of course they wished to save interest-and they withdrew more than $200,000 all in a day.

On Oct. 1 the bank had cash resources amounting to $966,530 with total assets of $3,910,891. By Nov. 21 the cash had shriveled away to $283,903 and the total resources to $2,742,907-and the big bank with its thousands of assets was as helpless as a child.

On Nov. 21, a committee of bankers from the Clearing House Association came in soberly by a side door, like physicians to a sick bed. They nosed through the ledgers, peered into the vaults and asked questions. Then they went away and decided that inasmuch as the old bank was soon to die, it better be put quietly out of its misery. The Clearing House Association wrote its death warrant, refusing to have any further transactions with it and resolving in formally worded resolutions that it be "suspended."

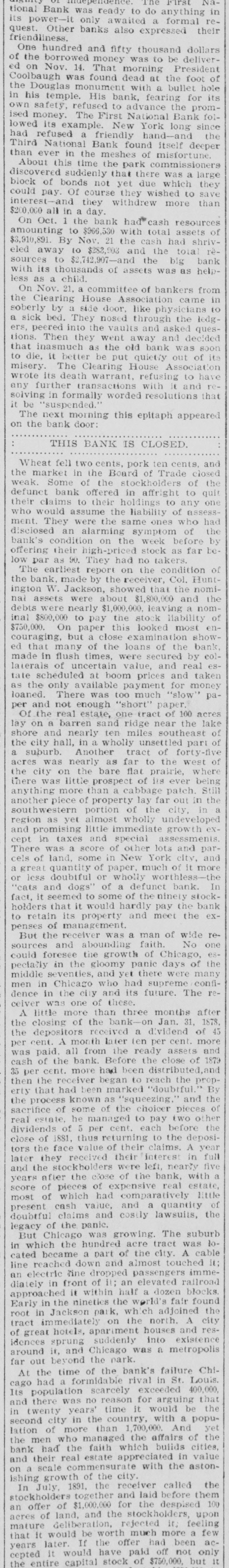

The next morning this epitaph appeared on the bank door:

THIS BANK IS CLOSED,

Wheat fell two cents, pork ten cents, and the market in the Board of Trade closed weak. Some of the stockholders of the defunct bank offered in affright to quit their claims to their holdings to any one who would assume the liability of assessment. They were the same ones who had disclosed an alarming symptom of the bank's condition on the week before by offering their high-priced stock as far below par as 90. They had no takers.

The earliest report on the condition of the bank, made by the receiver, Col. Huntington W. Jackson, showed that the nominal assets were about $1,800,000 and the debts were nearly $1,000,000, leaving a nominal $800,000 to pay the stock liability of $750,000. On paper this looked most encouraging, but a close examination showed that many of the loans of the bank, made in flush times, were secured by collaterals of uncertain value, and real estate scheduled at boom prices and taken as the only available payment for money loaned. There was too much "slow" paper and not enough "short" paper.

Of the real estate, one tract of 100 acres lay on a barren sand ridge near the lake shore and nearly ten miles southeast of the city hall, in a wholly unsettled part of a suburb. Another tract of forty-five acres was nearly as far to the west of the city on the bare flat prairie, where there was little prospect of its ever being anything more than a cabbage patch. Still another piece of property lay far out in the southwestern portion of the city, in a region as yet almost wholly undeveloped and promising little immediate growth except in taxes and special assessments. There was a score of other lots and parcels of land, some in New York city, and a great quantity of paper, much of it more or less doubtful or wholly worthless-the "cats and dogs" of a defunct bank. In fact, it seemed to some of the ninety stockholders that it would hardly pay the bank to retain its property and meet the expenses of management.

But the receiver was a man of wide resources and abounding faith. No one could foresee the growth of Chicago, especially in the gloomy panic days of the middle seventies, and yet there were many men in Chicago who had supreme confidence in the city and its future. The receiver was one of these.

A little more than three months after the closing of the bank-on Jan. 31, 1878, the depositors received a dividend of 45 per cent. A month later ten per cent. more was paid, all from the ready assets and cash of the bank. Before the close of 1879 35 per cent. more had been distributed, and then the receiver began to reach the property that had been marked "doubtful." By the process known as "squeezing," and the sacrifice of some of the choicer pieces of real estate, he managed to pay two other dividends of 5 per cent. each before the close of 1881, thus returning to the depositors the face value of their claims. A year later they received their interest in full and the stockholders were left, nearly five years after the close of the bank, with a score of pieces of expensive real estate, most of which had comparatively little present cash value, and a quantity of doubtful claims and costly lawsuits, the legacy of the panic.

But Chicago was growing. The suburb in which the hundred acre tract was located became a part of the city. A cable line reached down and almost touched it; an electric line dropped passengers immediately in front of it; an elevated railroad approached it within half a dozen blocks. Early in the nineties the world's fair found root in Jackson park, which adjoined the tract immediately on the north. A city of great hotels, apariment houses and residences sprung suddenly into existence around it, and Chicago was a metropolis far out beyond the park.

At the time of the bank's failure Chicago had a formidable rival in St. Louis. Its population scarcely exceeded 400,000, and there was no reason for arguing that in twenty years' time it would be the second city in the country, with a population of more than 1,700,000. And yet the men who managed the affairs of the bank had the faith which bulids cities, and their real estate appreciated in value on a scale commensurate with the astonishing growth of the city.

In July, 1891, the receiver called the stockholders together and laid before them an offer of $1,000,000 for the despised 100 acres of land, and the stockholders, upon mature deliberation, rejected it, feeling that it would be worth much more a few years later. If the offer had been accepted it would have paid off not only the entire capital stock of $750,000, but it