Article Text

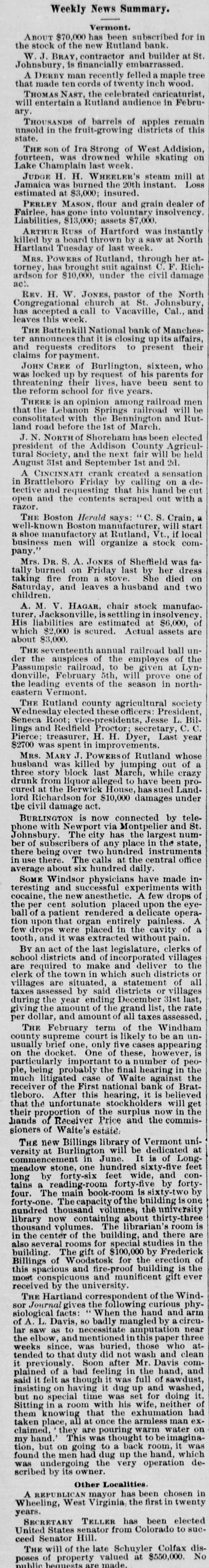

Weekly News Summary. Vermont. ABOUT $70,000 has been subscribed for in the stock of the new Rutland bank. W. J. BRAY, contractor and builder at St. Johnsbury, is financially embarrassed. A DERBY man recently felled a maple tree that made ten cords of twenty inch wood. THOMAS NAST, the celebrated caricaturist, will entertain a Rutland audience in February. THOUSANDS of barrels of apples remain unsold in the fruit-growing districts of this state. THE son of Ira Strong of West Addision, fourteen, was drowned while skating on Lake Champlain last week. JUDGE H. H. WHEELER'S steam mill at Jamaica was burned the 20th instant. Loss estimated at $3,000; insured. PERLEY MASON, flour and grain dealer of Fairlee, has gone into voluntary insolvency. Liabilities, $13,000; assets $7,000. ARTHUR Russ of Hartford was instantly killed by a board thrown by a saw at North Hartland Tuesday of last week. MRS. POWERS of Rutland, through her attorney, has brought suit against C. F. Richardson for $10,000, under the civil damage act. REV. H. W. JONES, pastor of the North Congregational church at St. Johnsbury, has accepted a call to Vacaville, Cal., and leaves this week. THE Battenkill National bank of Manchester announces that it is closing up its affairs, and requests creditors to present their claims for payment. JOHN CREE of Burlington, sixteen, who was locked up by request of his parents for threatening their lives, have been sent to the reform school for five years. THERE is an opinion among railroad men that the Lebanon Springs railroad will be consolitated with the Bennington and Rutland road before the 1st of March. J. N. NORTH of Shoreham has been elected president of the Addison County Agricultural Society, and the next fair will be held August 31st and September 1st and 2d. A CINCINNATI crank created a sensation in Brattleboro Friday by calling on a detective and requesting that his hand be cut open and the contents scraped out with a razor. THE Boston Herald says: "C. S. Crain, a well-known Boston manufacturer, will start a shoe manufactory at Rutland, Vt., if local business men will organize a stock company." Mrs. DR. S. A. JONES of Sheffield was fatally burned on Friday last by her dress taking fire from a stove. She died on Saturday, and leaves a husband and two children. A. M. V. HAGAR, chair stock manufacturer, Jacksonville, issettling in insolvency. His liabilities are estimated at $6,000, of which $2,000 is scured. Actual assets are about $3,000. THE seventeenth annual railroad ball under the auspices of the employes of the Passumpsic railroad, to be given at Lyndonville, February 5th, will prove one of the leading events of the season in northeastern Vermont. THE Rutland county agricultural society Wednesday elected these officers: President, Seneca Root: vice-presidents, Jesse L. Billings and Redfield Proctor: secretary, C. C. Pierce: treasurer, H. H. Dyer, Last year $2700 was spent in improvements. MRS. MARY J. POWERSOf Rutland whose husband was killed by jumping out of a three story block last March, while crazy drunk from liquor alleged to have been procured at the Berwick House, has sued Landlord Richardson for $10,000 damages under the civil damage act. BURLINGTON is now connected by telephone with Newport via Montpelier and St. Johnsbury. The city has the largest number of subscribers of any place in the state, there being over two hundred instruments in use there. The calls at the central office average about six hundred daily. SOME Windsor physicians have made interesting and successful experiments with cocaine, the new anesthetic. A few drops of the per cent solution placed upon the eyeball of a patient rendered a delicate operation upon that organ entirely painless. A a few drops were placed in the cavity of tooth, and it was extracted without pain. By an act of the last legislature, clerks of school districts and of incorporated villages are required to make and deliver to the clerk of the town in which such districts or villages are situated, a statement of all taxes assessed by said districts or villages during the year ending December 31st last, giving the amount of the grand list, the rate per dollar, and amount of all taxes assessed. THE February term of the Windham county supreme court is likely to be an unusually brief one, only five cases appearing on the docket. One of these, however, is particularly important to a number of people, being probably the final hearing in the much litigated case of Waite against the receiver of the First national bank of Brattleboro. After this hearing, it is believed that the unfortunate stockholders will get their proportion of the surplus now in the hands of Receiver Price and the commissioners of Waite's estate. THE new Billings library of Vermont university at Burlington will be dedicated at commencement in June. It is of Longmeadow stone, one hundred sixty-five feet long by forty-six feet wide, and contains a reading-room forty-five by fortyfour. The main book-room is sixty-two by forty-one. The capacity of the building is one nundred thousand volumes, the university library now containing about thirty-three thousand volumes. The librarian's room is in the center of the building, and there are also several rooms for special studies in the building. The gift of $100,000 by Frederick Billings of Woodstosk for the erection of this spacious and fire-proof building is the most conspicuous and munificent gift ever received by the university. THE Hartland correspondent of the Windsor Journalgives the following curious physiological facts: When the hand and arm of A. L. Davis, 80 badly mangled by a circular saw as to necessitate amputation near the elbow, and mentioned in this paper three weeks since, was buried, those who attended to that duty did not wash and clean it previously. Soon after Mr. Davis complained of a bad feeling in the hand, and said it felt as though it was full of sawdust, insisting on having it dug up and washed, but no special time was set for doing it.