Article Text

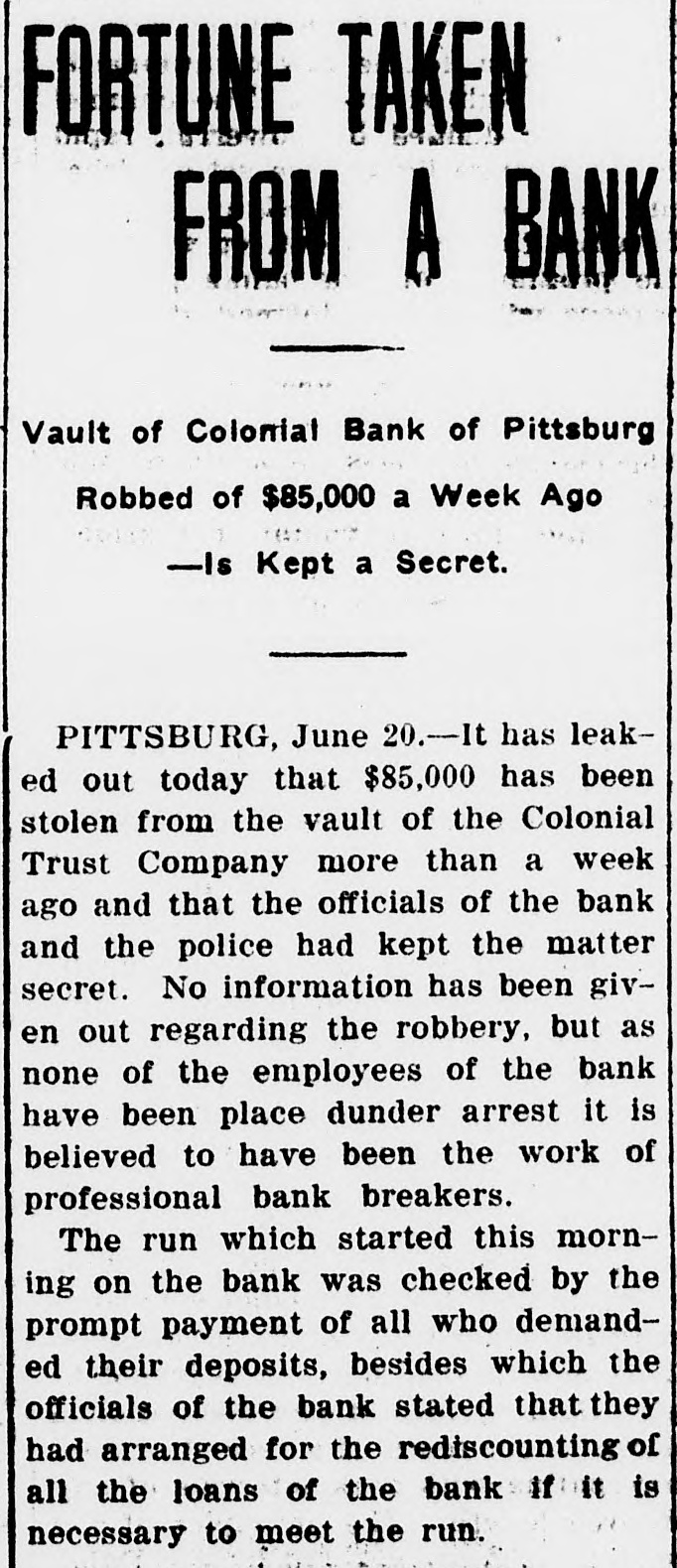

FORTUNE TAKEN FROM A BANK Vault of Colonial Bank of Pittsburg Robbed of $85,000 a Week Ago -Is Kept a Secret. PITTSBURG, June 20.-It has leaked out today that $85,000 has been stolen from the vault of the Colonial Trust Company more than a week ago and that the officials of the bank and the police had kept the matter secret. No information has been given out regarding the robbery, but as none of the employees of the bank have been place dunder arrest it is believed to have been the work of professional bank breakers. The run which started this morning on the bank was checked by the prompt payment of all who demanded their deposits, besides which the officials of the bank stated that they had arranged for the rediscounting of all the loans of the bank if it is necessary to meet the run.