Article Text

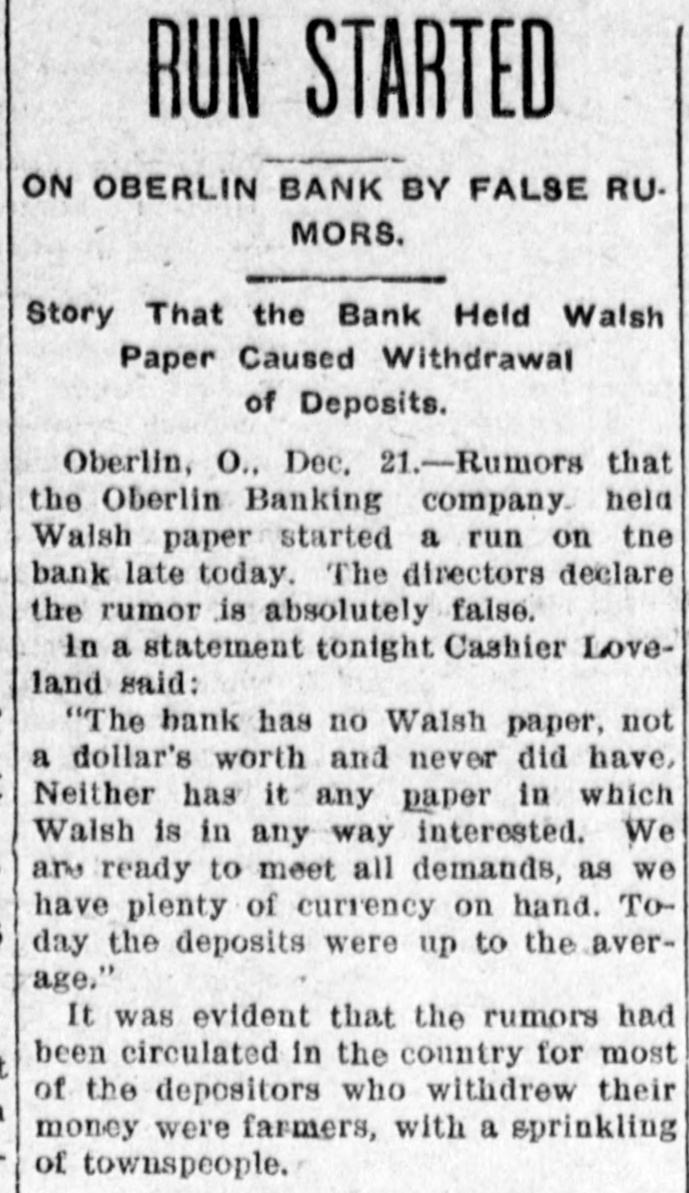

Disclosure of Doings of the Chadwicks Expected In Cleveland. WOMAN FOUND IN NEW YORK Hubby Has Probably Scuttled For Europe-Suit of Massachusetts Banker Caused Closing of Bank at OberlinAlleged Noted Men Are Implicated. Cleveland, O., Nov. 29.-The Chadwick case has closed a bank in Oberlin and caused runs on several banks in Cleveland. Mrs. Chadwick, who vanished from Cleveland on Thurs: day, has been located in New York. Chadwick is believed to have scuttled to Europe. Banker Newton expects to be in Cleveland today when his case against Mrs. Chadwick is called in court. Amazing tales of gullibility of financiers and misuse of world-famous names are promised. These are the latest developments in the astonishing Chadwick sensation, which promises to eclipse every other swindling case ever unearthed in this country. These are the cases against Mrs Chadwick, to come up at once in Cleveland, starting with the Newton case: Several Cases. Herbert Newton, banker, Brookline. Mass., sues for $190,000, loaned on worthless notes and pretenses to possession of $5,000,000 invested in securitles in New York and $2,500,000 in real property elsewhere, none of which has any known existence. Euclid Avenue Savings Co., Cleveland, sues to recover on notes for $58,231. Savings Deposit Bank & Trust Co., Elyria, O., sues for $10,000. American Exchange National bank sues on notes for $28,808. How much the Oberlin bank was "let down" for is not known, as it has not yet begun suit. It sustained a small run Saturday and shut its doors Monday. Disclosures Promised. Great interest is manifested in the hearing to begin in the common pleas court here today on a motion to have a receiver named to take charge of the alleged securities said to be in custody of Iri Reynolds at the Wade Park bank, on which Mrs. C. L. Chadwick secured various sums from banks in this city and elsewhere. The attorney for Herbert L. Newton of Brookline, Mass., arrived here last night and seems confident that Mrs. Chadwick will settle before the hour of hearing arrives. He says if she does not there will be some startling disclosures. The officials of the Oberlin bank that closed because of loans made to Mrs. Chadwick say they expect a large sum today, and if it is not forthcoming threaten sensational disclosures. Mrs. Chadwick claims that one note for $500,000 is signed by one of the richest men in the country, and bankers who have seen this and other notes call them gild-edged security. Late last night President Beckwith of the Oberlin bank admitted that he had aided Mrs. Chadwick in getting loans aggregating $102,000.