Click image to open full size in new tab

Article Text

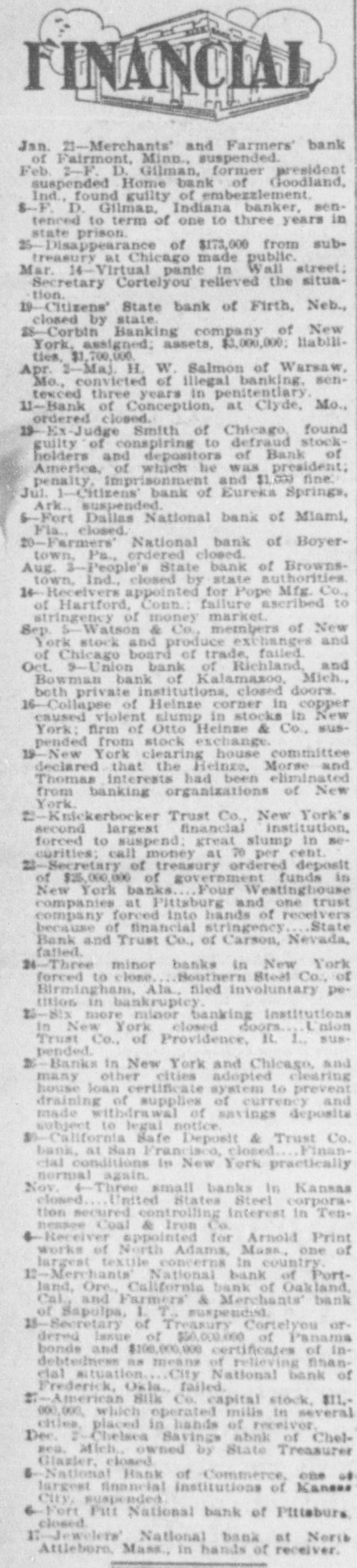

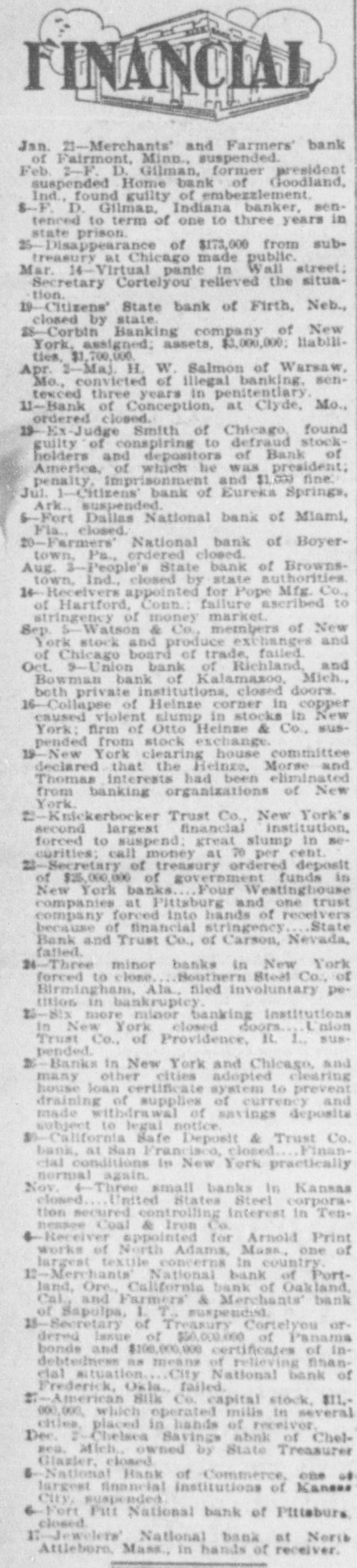

FINANCIAL Jan. 21-Merchants' and Farmers' bank of Fairmont, Minn., suspended. Feb. 2-F. D. Gilman, former president suspended Home bank of Goodland, Ind., found guilty of embezzlement. 8-F. D. Gilman, Indiana banker, sentenced to term of one to three years in state prison. $-Disappearance of $173,000 from subtreasury at Chicago made public. Mar. 14-Virtual pante in Wall street; Secretary Cortelyou relieved the situation. 19-Citizens' State bank of Firth, Neb., closed by state. IS-Corbin Banking company of New York, assigned; assets, $3,000,000: Habillties, $1,700,000 Apr. 2-Maj. H. W. Salmon of Warsaw, Mo., convicted of illegal banking. sentexced three years in penitentiary. 11-Bank of Conception, at Clyde, Mo., ordered closed. 19-Ex-Judge Smith of Chicago, found guilty of conspiring to defraud stockholders and depositors of Bank of America. of which he was president; penalty, Imprisonment and $1,000 fine. Jul. 1-Citizens' bank of Eureka Springs, Ark., suspended. &-Fort Dallas National bank of Miami, Fla., closed. 20-Farmers' National bank of Boyertown. Pa., ordered closed. Aug. 3-People's State bank of Brownstown, Ind., closed by state authorities It Receivers appointed for Pope Mfg. Co., of Hartford, Conn.: failure ascribed to stringency of money market. Sep -Watson & Co., members of New York stock and produce exchanges and of Chicago board of trade, failed. Oct. 9-Union bank of Richland, and Bowman bank of Kalamazoo, Mich., both private institutions, closed doors. 16-Collapse of Heinze corner in copper caused violent slump in stocks in New York: firm of Otto Heinze & Co., suspended from stock exchange. I9-New York clearing house committee declared that the Heinre, Morse and Thomas interests had been eliminated from banking organizations of New York. -Knickerbocker Trust Co., New York's second largest financial institution, forced to suspend; great stump In securities: call money at 20 per cent. 23-Secretary of treasury ordered deposit of $15,000,000 of government funds in New York banks. Four Westinghouse companies at Pittsburg and one trust company forced into hands of receivers because of financial stringency State Bank and Trust Co., of Carson, Nevada, falled. 14-Three minor banks in New York forced to close. Bouthern Steel Co., of Birmingham, Ala., filed Involuntary petitlon in bankruptcy. more minor banking institutions In New York closed doors Union Trust Co., of Providence, R. 1., suspended. 26 Banks in New York and Chicago, and many other cities adopted clearing house loan certificate system to prevent draining of supplies of currency and made withdrawal of savings deposits subject to legal notice $9 0-California Safe Deposit & Trust Co. bank. at Ban Francisco, closed Financlal conditions in New York practically normal again. Nov. 4-Three small banks In Kansas closed United States Steel corporation secured controlling interest in Tennessee Coal & Iron Co. -Receiver appointed for Arnold Print works of North Adams, Muss, one of largest textile concerns in country. If-Merchants National bank of Portland, Ore, California bank of Oakland, Cal. and Farmers' & Merchants' bank of Sapulpa, LT, suspended. 15 -Secretary of Treasury Cortelyou ordered Issue of $50,000,000 of Panama bonds and $108,000,000 certificates of indebtedness na means of relieving finandal situation City National bank of Frederick, Okla., failed. IT-American Hilk Co. capital stock, $11,000,000, which operated mills in several cities, placed in hands of receiver Dec. Chelsea Savings abnk of Chelnea. Mich, owned by State Treasurer Glazier, closed. National Bank of Commerce, one of largest financial institutions of Manage CITY, suspended Fort Fill National bank of Pittsburs closed K-Jewelers' National bank at North Attleboro, Mass., in hands of receiver.