Article Text

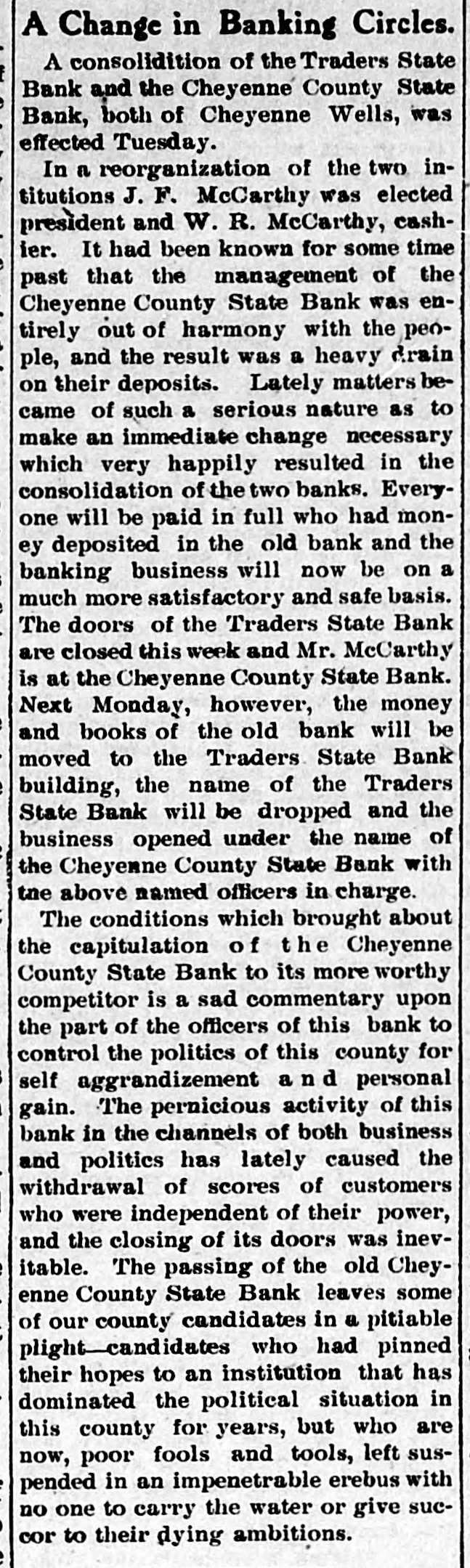

A Change in Banking Circles. A consolidition of the Traders State Bank and the Cheyenne County State Bank, both of Cheyenne Wells, was effected Tuesday. In a reorganization of the two intitutions J. F. McCarthy was elected president and W. R. McCarthy, cashier. It had been known for some time past that the management of the Cheyenne County State Bank was entirely out of harmony with the penple, and the result was a heavy drain on their deposits. Lately matters became of such a serious nature as to make an immediate change necessary which very happily resulted in the consolidation of the two banks. Everyone will be paid in full who had money deposited in the old bank and the banking business will now be on a much more satisfactory and safe basis. The doors of the Traders State Bank are closed this week and Mr. McCarthy is at the Cheyenne County State Bank. Next Monday, however, the money and books of the old bank will be moved to the Traders State Bank building, the name of the Traders State Bank will be dropped and the business opened under the name of the Cheyenne County State Bank with the above named officers in charge. The conditions which brought about the capitulation of the Cheyenne County State Bank to its more worthy competitor is a sad commentary upon the part of the officers of this bank to control the politics of this county for self aggrandizement and personal gain. The pernicious activity of this bank in the channels of both business and politics has lately caused the withdrawal of scores of customers who were independent of their power, and the closing of its doors was inevitable. The passing of the old Cheyenne County State Bank leaves some of our county candidates in a pitiable plight-candidates who had pinned their hopes to an institution that has dominated the political situation in this county for years, but who are now, poor fools and tools, left suspended in an impenetrable erebus with no one to carry the water or give succor to their dying ambitions.