Article Text

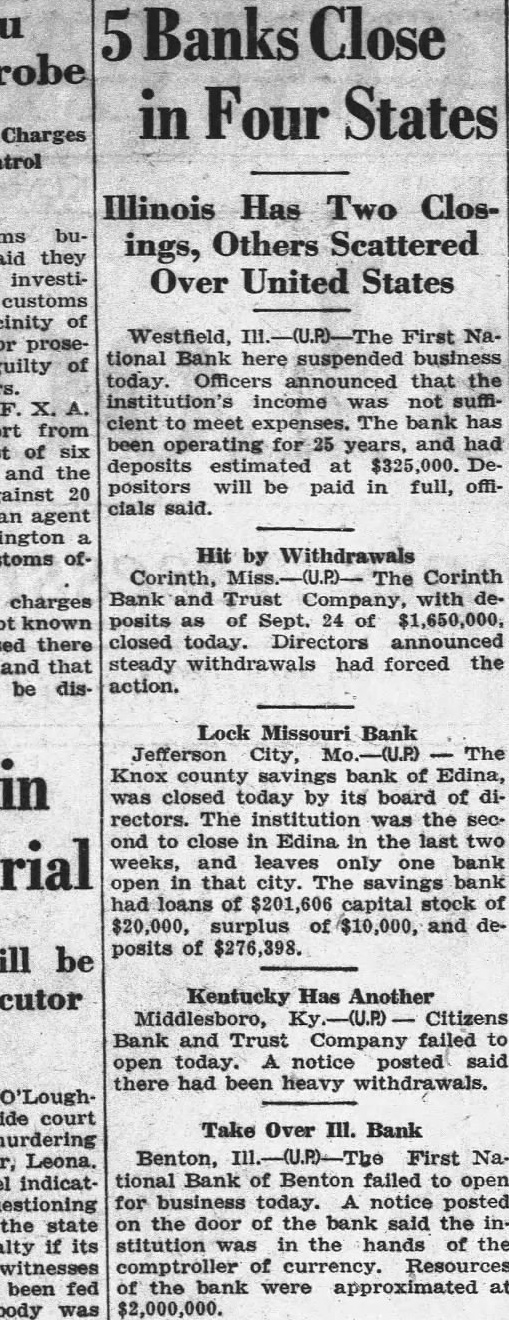

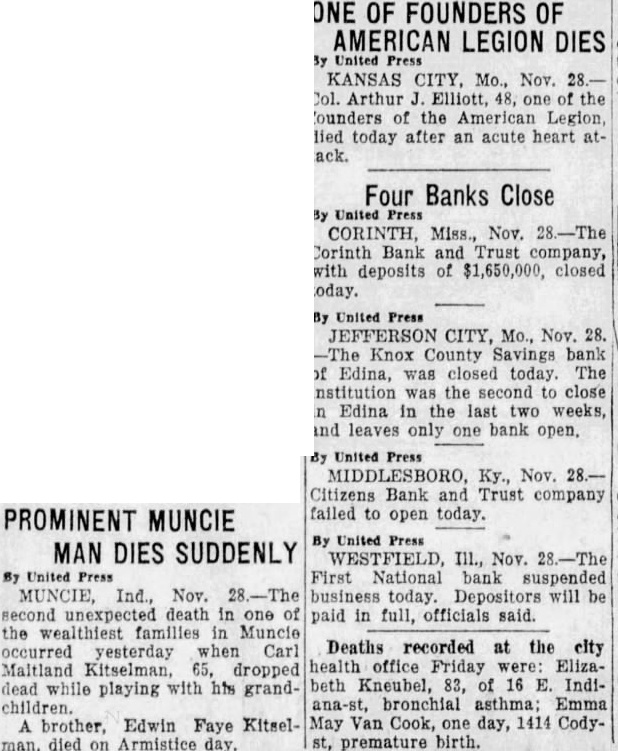

Banks Close in Four States Illinois Has Two Closings, Others Scattered Over United States Westfield, III.-(U.P)-The First National Bank here suspended business today. Officers announced that the institution's income was not sufficient to meet expenses. The bank has been operating for 25 years, and had deposits estimated at $325,000. Depositors will be paid in full, officials said. Hit by Withdrawals Corinth, Miss. The Corinth Bank and Trust Company, with deposits as of Sept. 24 of $1,650,000, closed today. Directors announced steady withdrawals had forced the action. Lock Missouri Bank Jefferson City, -(U.P.) The Knox county savings bank of Edina, was closed today by its board of directors. The institution was the second to close in Edina in the last two weeks, and leaves only one bank open in that city. The savings bank had loans of $201,606 capital stock of $20,000, surplus of $10,000, and deposits of $276,398. Kentucky Has Another Middlesboro, Ky.-(U.P.) Citizens Bank and Trust Company failed to open today. A notice posted said there had been heavy withdrawals. Take Over III. Bank Benton, Ill.-(U.P)-The First Na. tional Bank of Benton failed to open for business today. A notice posted on the door of the bank said the institution was in the hands of the comptroller of currency. Resources of the bank were approximated at $2,000,000.