Click image to open full size in new tab

Article Text

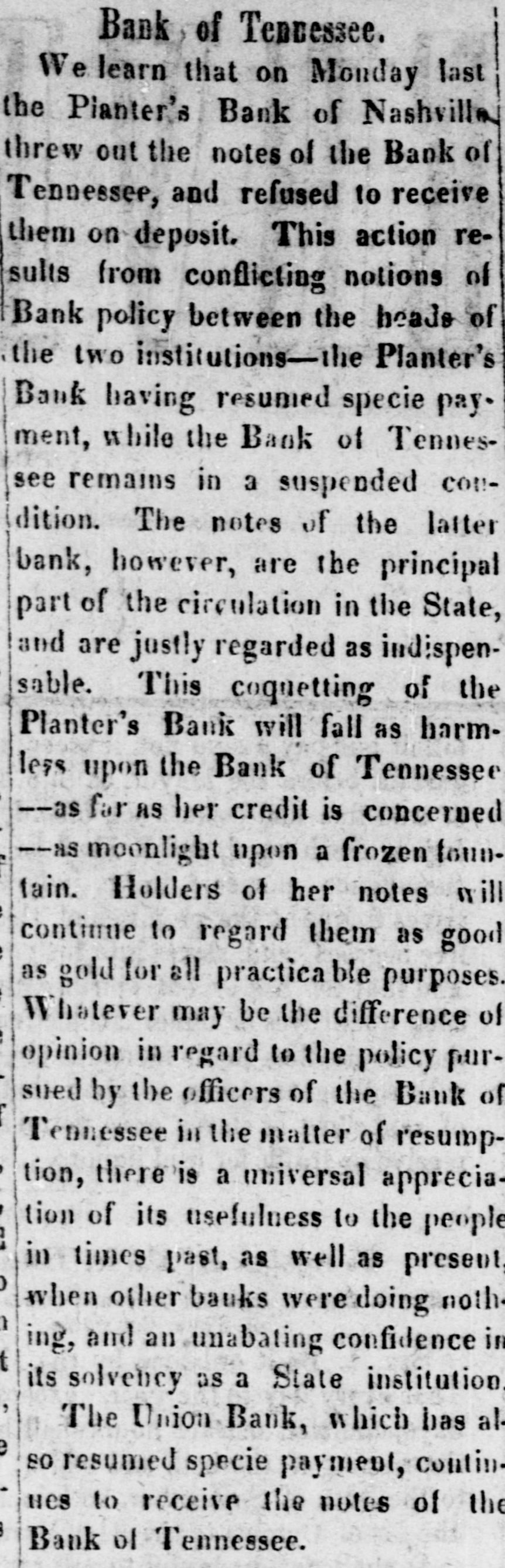

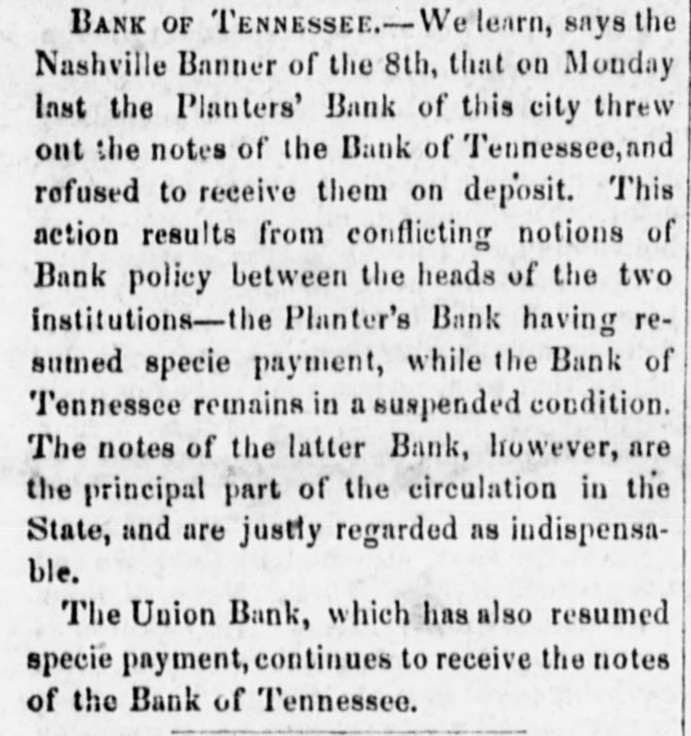

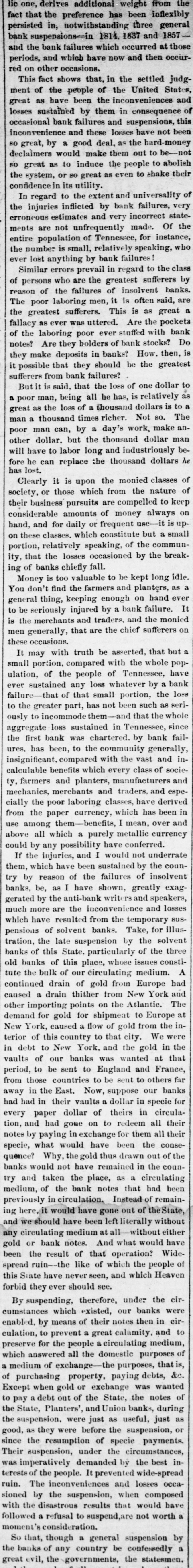

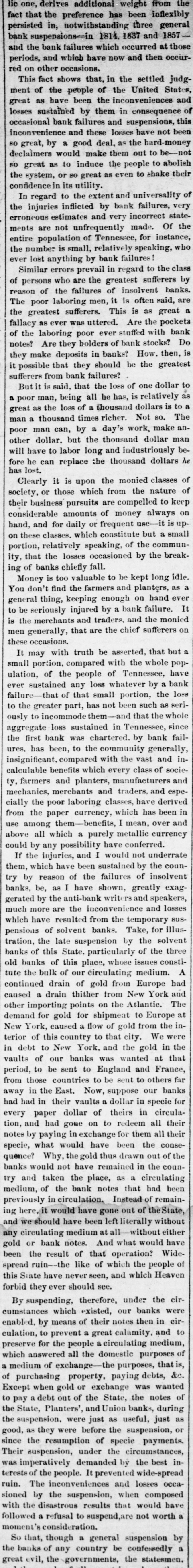

lic one, derives additional weight from the

fact that the preference has been inflexibly

persisted in, notwithstanding three general

bank suspensions—in 1814, 1837 and 1857—

and the bank failures which occurred at those

periods, and which have now and then occur-

red on other occasions.

This fact shows that, in the settled judg-

ment of the people of the United States,

great as have been the inconveniences and

losses sustained by them in consequence of

occasional bank failures and suspensions, this

inconvenience and these losses have not been

so great, by a good deal, as the hard-money

declaimers would make them out to be—not

so great as to induce the people to abolish

the system, or so great as even to shake their

confidence in its utility.

In regard to the extent and universality of

the injuries inflicted by bank failures, very

erroneous estimates and very incorrect state-

ments are not unfrequently made. Of the

entire population of Tennessee, for instance,

the number is small, relatively speaking, who

ever lost anything by bank failures!

Similar errors prevail in regard to the class

of persons who are the greatest sufferers by

reason of the failures of insolvent banks.

The poor laboring men, it is often said, are

the greatest sufferers. This is as great a

fallacy as ever was uttered. Are the pockets

of the laboring poor ever stuffed with bank

notes? Are they holders of bank stocks? Do

they make deposits in banks? How, then, is

it possible that they should be the greatest

sufferers from bank failures?

But it is said, that the loss of one dollar to

a poor man, being all he has, is relatively as

great as the loss of a thousand dollars is to a

man a thousand times richer. Not so. The

poor man can, by a day's work, make an-

other dollar, but the thousand dollar man

will have to labor long and industriously be-

fore he can replace the thousand dollars he

has lost.

Clearly it is upon the monied classes of

society, or those which from the nature of

their business pursuits are compelled to keep

considerable amounts of money always on

hand, and for daily or frequent use—it is up-

on these classes, which constitute but a small

portion, relatively speaking, of the commun-

ity, that the losses occasioned by the break-

ing of banks chiefly fall.

Money is too valuable to be kept long idle.

You don't find the farmers and planters, as a

general thing, keeping enough on hand ever

to be seriously injured by a bank failure. It

is the merchants and traders, and the monied

men generally, that are the chief sufferers on

these occasions.

It may with truth be asserted, that but a

small portion, compared with the whole pop-

ulation, of the people of Tennessee, have

ever sustained any loss whatever by a bank

failure—that of that small portion, the loss

to the greater part, has not been such as seri-

ously to incommode them—and that the whole

aggregate loss sustained in Tennessee, since

the first bank was chartered, by bank fail-

ures, has been, to the community generally,

insignificant, compared with the vast and in-

calculable benefits which every class of socie-

ty, farmers and planters, manufacturers and

mechanics, merchants and traders, and espe-

cially the poor laboring classes, have derived

from the paper currency, which has been in

use among them—benefits, I mean, over and

above all which a purely metallic currency

could by any possibility have conferred.

If the injuries, and I would not underrate

them, which have been sustained by the coun-

try by reason of the failures of insolvent

banks, be, as I have shown, greatly exag-

gerated by the anti-bank writers and speakers,

much more are the inconvenience and losses

which have resulted from the temporary sus-

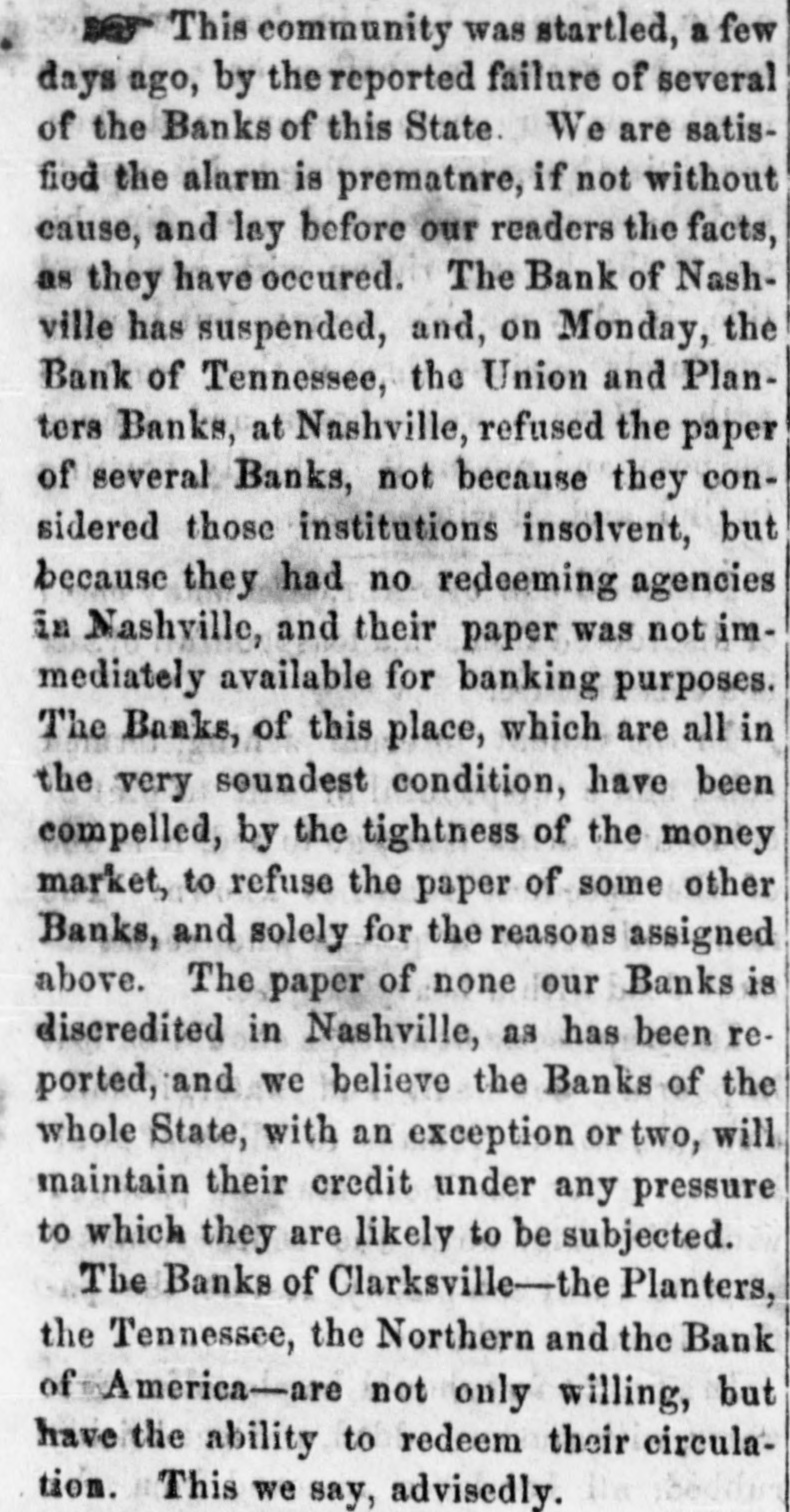

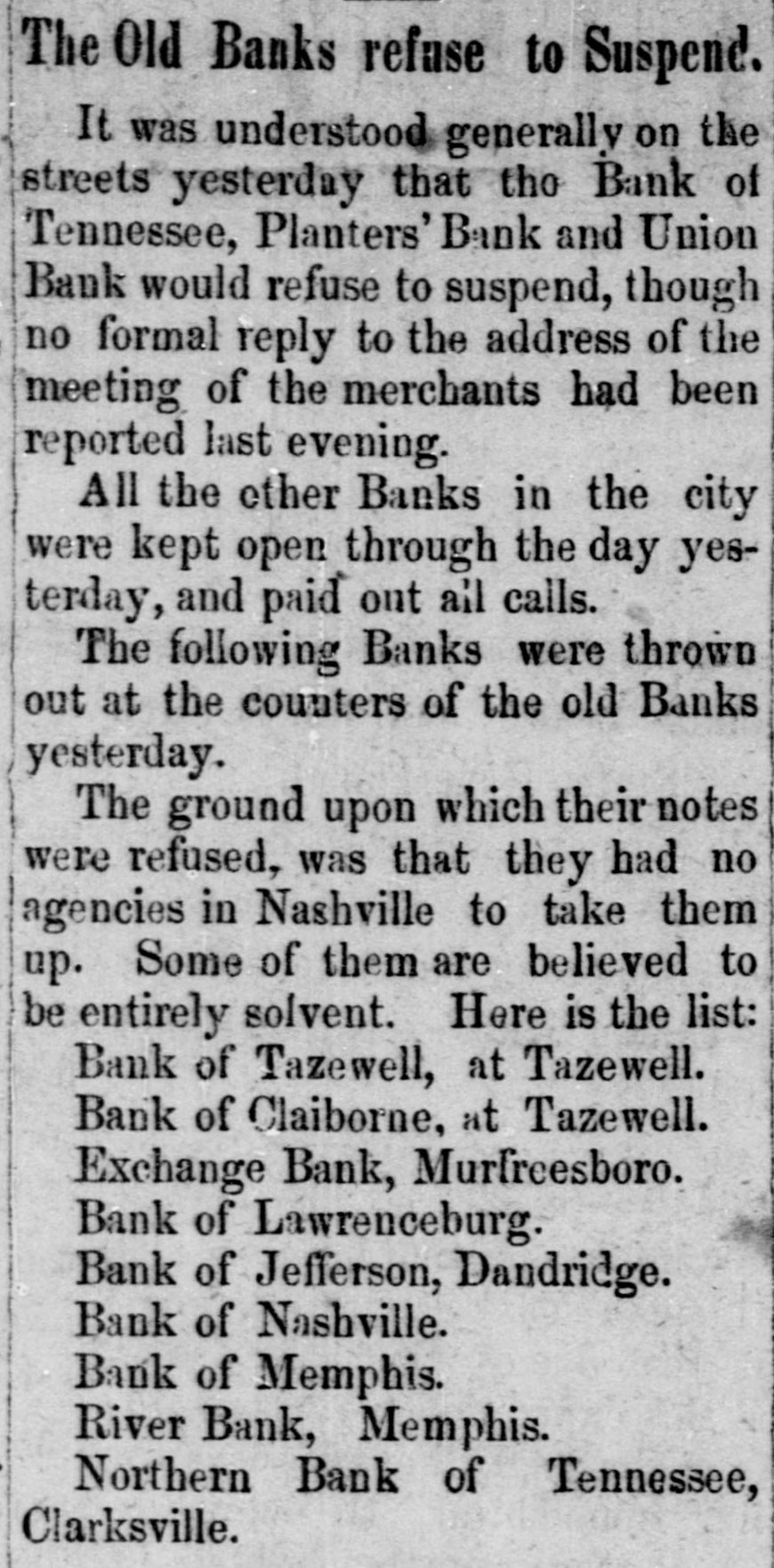

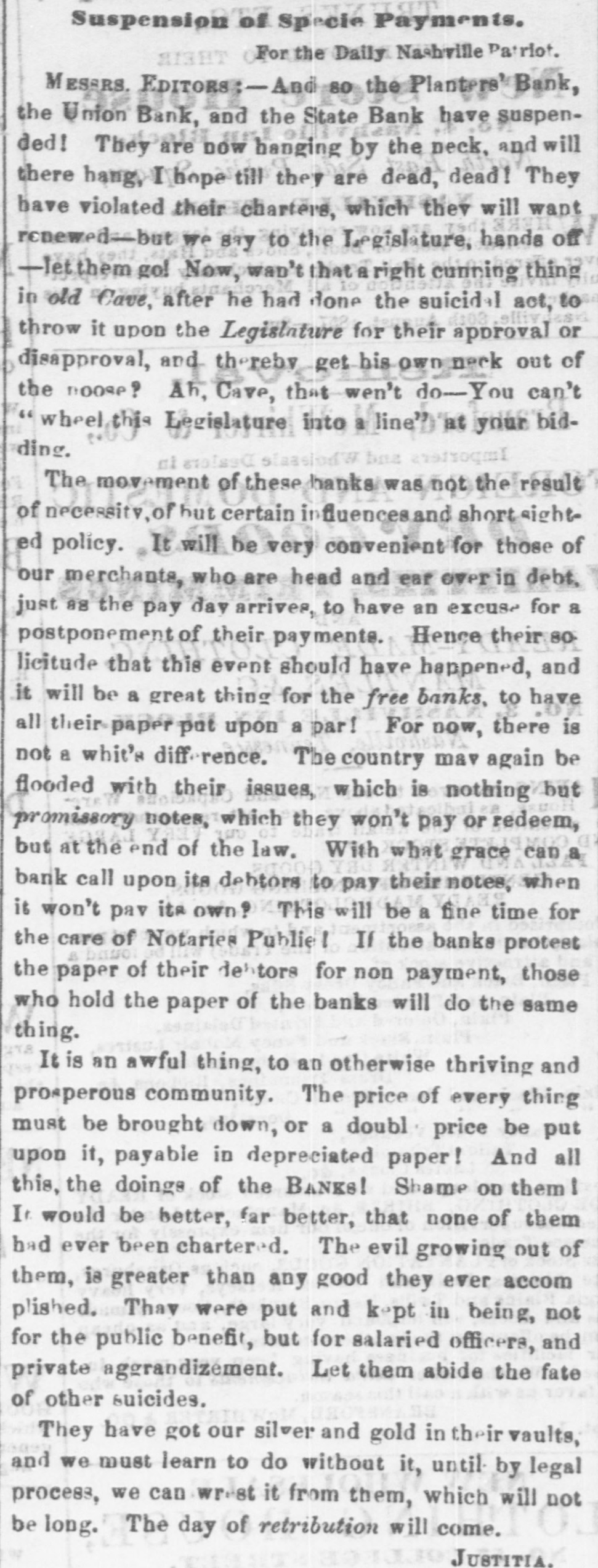

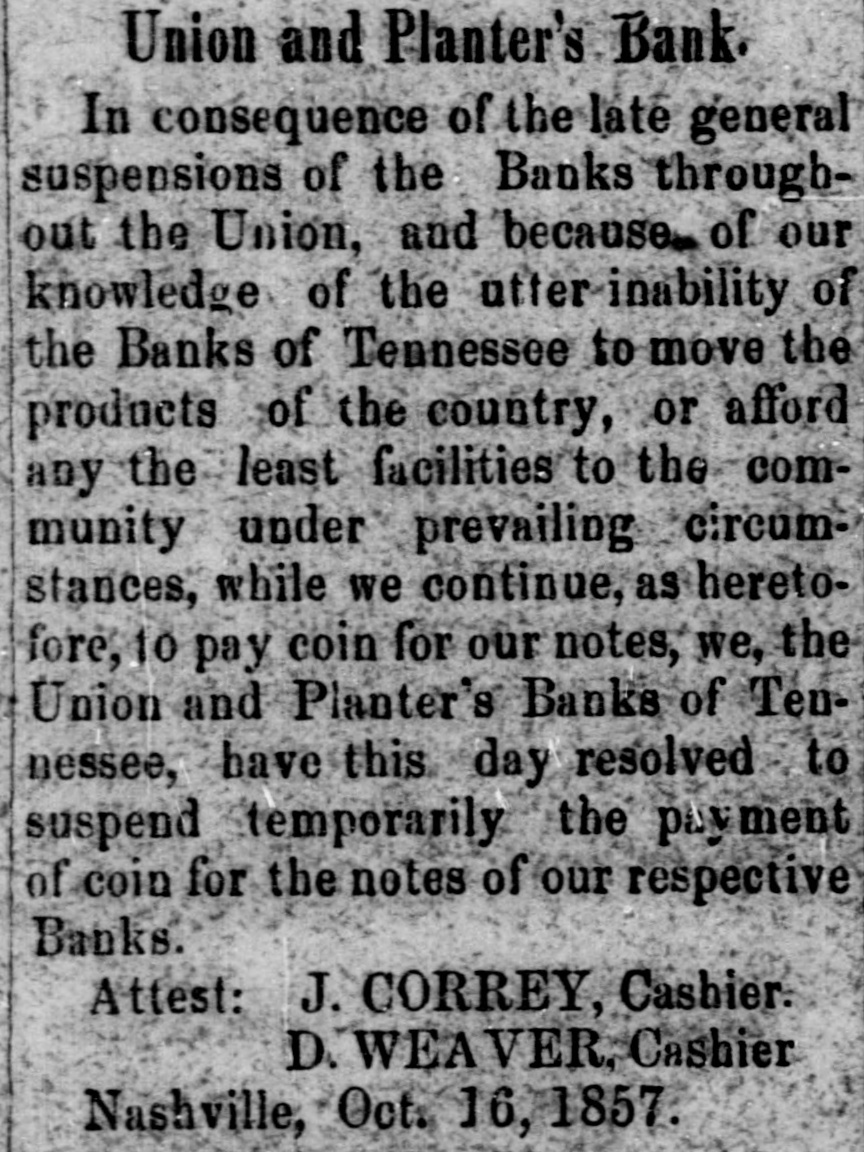

pensions of solvent banks. Take, for illus-

tration, the late suspension by the solvent

banks of this State, particularly of the three

old banks of this place, whose issues consti-

tute the bulk of our circulating medium. A

continued drain of gold from Europe had

caused a drain thither from New York and

other importing points on the Atlantic. The

demand for gold for shipment to Europe at

New York, caused a flow of gold from the in-

terior of this country to that city. We were

in debt to New York, and the gold in the

vaults of our banks was wanted at that

period, to be sent to England and France,

from those countries to be sent to others far

away in the East. Now, suppose our banks

had had in their vaults a dollar in specie for

every paper dollar of theirs in circula-

tion, and had gone on to redeem all their

notes by paying in exchange for them all their

specie, what would have been the conse-

quence? Why, the gold thus drawn out of the

banks would not have remained in the coun-

try and taken the place, as a circulating

medium, of the bank notes that had been

previously in circulation. Instead of remain-

ing here, it would have gone out of the State,

and we should have been left literally without

any circulating medium at all—without either

gold or bank notes. And what would have

been the result of that operation? Wide-

spread ruin—the like of which the people of

this State have never seen, and which Heaven

forbid they ever should see.

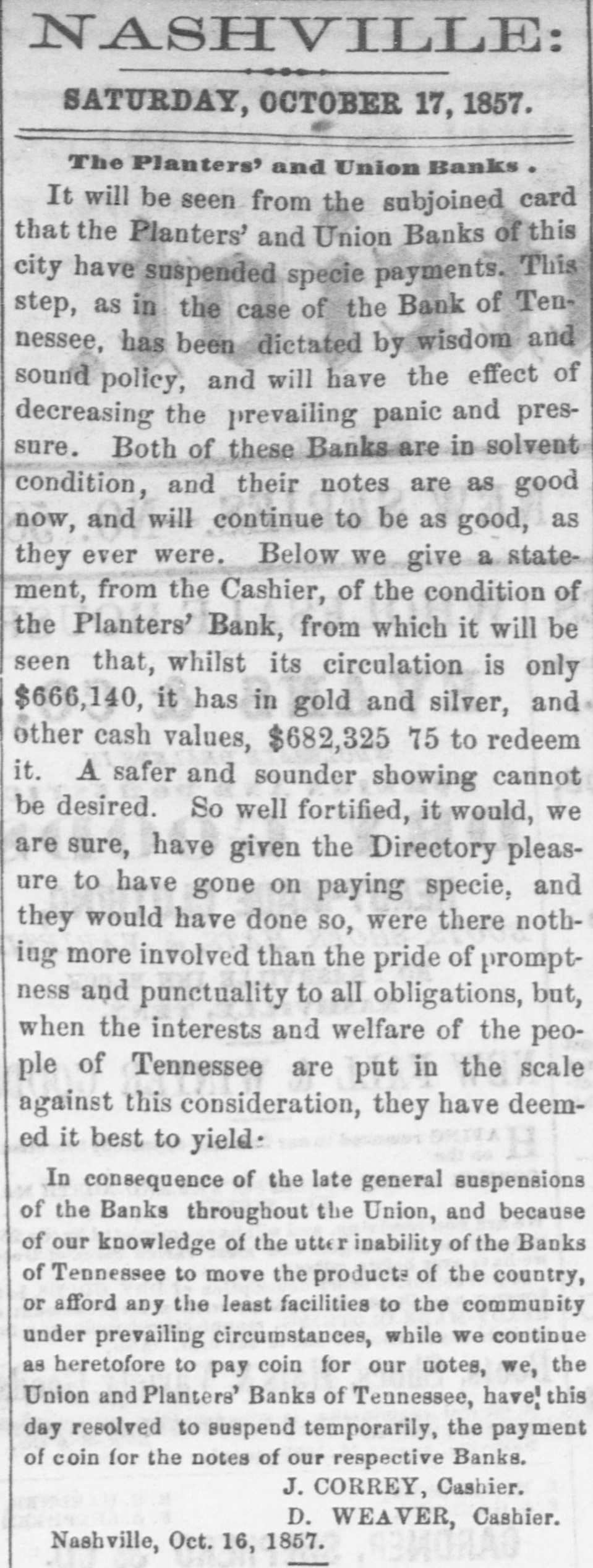

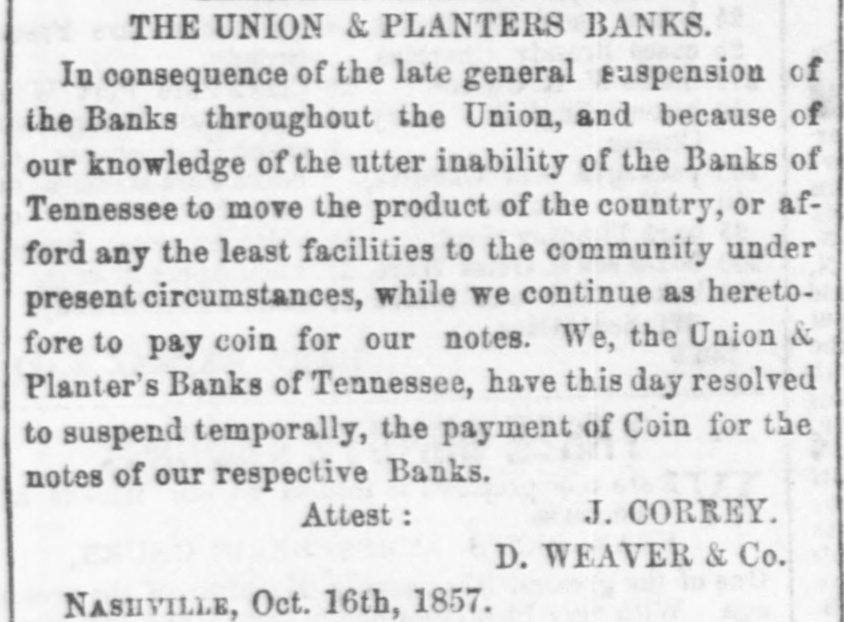

By suspending, therefore, under the cir-

cumstances which existed, our banks were

enabled, by means of their notes then in cir-

culation, to prevent a great calamity, and to

preserve for the people a circulating medium,

which answered all the domestic purposes of

a medium of exchange—the purposes, that is,

of purchasing property, paying debts, &c.

Except when gold or exchange was wanted

to pay a debt out of the State, the notes of

the State, Planters', and Union banks, during

the suspension, were just as useful, just as

good, as they were before the suspension, or

since the resumption of specie payments.

Their suspension, under the circumstances,

was imperatively demanded by the best in-

terests of the people. It prevented wide-spread

ruin. The inconveniences and losses occa-

sioned by the suspension, when composed

with the disastrous results that would have

followed a refusal to suspend, are not worth a

moment's consideration.

So that, though a general suspension by

the banks of any country be confessedly a

great evil, the governments, the statesmen.