Click image to open full size in new tab

Article Text

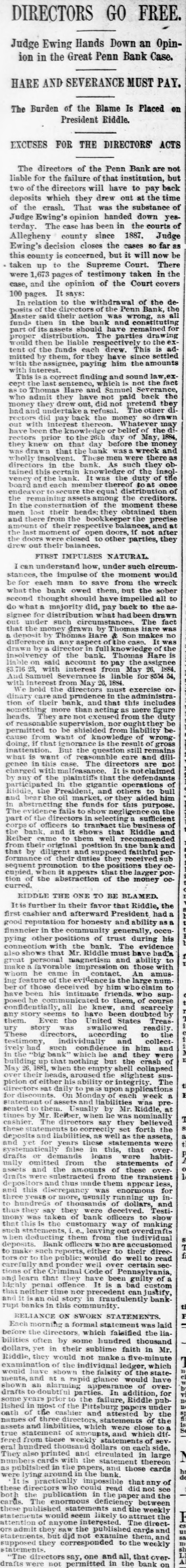

DIRECTORS GO FREE. Judge Ewing Hands Down an Opinion in the Great Penn Bank Case. HARE AND SEVERANCE MUST PAY. The Burden of the Blame Is Placed on President Riddle. EXCUSES FOR THE DIRECTORS' ACTS The directors of the Penn Bank are not liable for the failure of that institution, but two of the directors will have to pay back deposits which they drew out at the time of the crash. That was the substance of Judge Ewing's opinion handed down yesterday. The case has been in the courts of Allegheny county since 1887. Judge Ewing's decision closes the cases so far as this county is concerned, but it will now be taken up to the Supreme Court. There were 1,673 pages of testimony taken in the case, and the opinion of the Court covers 100 pages. It says: In relation to the withdrawal of the deposits of the directors of the Penn Bank, the Master said their action was wrong, as all funds then in the bank and constituting part of its assets should have remained for proper distribution. The parties drawing would then be liable respectively to the extent of the funds each drew. This is admitted by them, for they have since settled with the assignee, paying him the amounts interest. with This is correct finding and sound law,except the last sentence, which is not the fact as to Thomas Hare and Samuel Severance, who admit they have not paid back the money they drew out, did not pretend they had and undertake a refusal. The other directors did pay back the money so drawn out with interest thereon. Whatever may have been the knowledge or belief of the directors prior to the 26th day of May, 1884, they knew on that day before the money was drawn that the bank was wreck and wholly insolvent. These men were there as directors in the bank. As such they obtained this certain knowledge of the insolvency of the bank. It was the duty of the board and each member thereof toat once endea the equal distribution of the remaining assets among the creditors. In the consternation of the moment these men lost their heads: they obtained then and there from the bookkeeper the precise amount of their respective balances, and at the last moment of open doors, if not after the doors were closed to other parties, they drew out their balances. FIRST IMPULSES NATURAL. I can understand how, under such circumstances, the impulse of the moment would be for each man to save from the wreck what the bank owed them, but the sober second thought should have impelled all to do what a majority did, pay back to the assignee for distribution what had been drawn out under such circumstances. The fact that the money drawn by Thomas Hare was a deposit by Thomas Hare & Son makes no difference in any aspect of the case. It was drawn by a director in full knowledge of the insolvency of the bank. Thomas Hare is liable on said account to pay the assignee $3 716 23, with interest from May 26, 1884. And Samuel Severance is liable for $554 54, with interest from May 26, 1884. We hold the directors must exercise ordinary care and prudence in the administration of their bank, and that this includes something more than acting as mere figure heads. They are not excused from the duty of reasonable supervision, nor ought they be permitted to be shielded from liability because from want of knowledge of wrong. doing, if that ignorano is the result of gross inattention. But the question still remains what is want of reasonable care and diligence in this case The directors are not charged with malfeasance It is not claimed by any of the plaintiffs that the defendants participated in the gigantic operations of Riddle, the President, and others to bull and bear the oil market, or they aided him in abstracting the funds for this purpose. The evidence fails to show negligenc on the part of the directors in selecting sufficient corps of officers to transact the business of the bank, and it shows that Riddle and Reiber came to them well recommended from their original position in the bank and that by diligent and supposed faithful performance of their duties they received sub seguent promotion to the positions they occupied, when it appears that the larger portion of the abstraction of the money occurred. RIDDLE THE ONE TO BE BLAMED. Itis further in their favor that Riddle, the first cashier and afterward President had a good reputation for honesty and ability as a financier in the community generally, occupying other positions of trust during his connection with the bank. The evidence also shows that Mr. Riddle must have bad'a great personal magnetism and ability to make favorable impression on those with R whom he came in contact. An amusing feature of the evidence is the large number of those deceived by him who claim to have been his intimate friends. who supposed he municated to them, of course confidentially all he knew, and scarcely any story seems to have been doubted by them. Even the United States Treasury story was swallowed readily the These directors, according to testimony, individually and collectively had such confidence in him and in the "big bank' which he and they were building up that nothing but the crash of May 26, 1881 when the empty shell collapsed over their heads, aroused the slightest suspicion of either his ability or integrity The t directors sat daily to S8 upon applications E for discounts. On Monday of each week a statement assets and liabilities was presented to them Usually by Mr. Riddle, at times by Mr. Reiber, hen he was nominally T cashier The directors say they believed these to correctly set forth the deposits and liabilities, ns well as the assets, and yet for years these statements were systematically false in this, that over P drafts or demands loans were habitually omitted from the statements of assets and the amounts of these overdrafts were from the transient pos and thus made them appear less, and this discrepancy was enormous for three years or more, usually running up into hundreds of thousands of dollars, and thus they say they were deceived. Testimony was taken of bank officers to show that this is the customary way of making such statements, 1. leaving out overdraf hen deducting them from the individual deposits. Bank officers who are accustomed to make such reports, either to their direcfi tors or to the public: would do well to read carefully and ponder well over certain sections of the iminal Code of Pennsylvania, and learn that they have been guilty of a highly penal offence It is a bad custom that neither time nor precedent can justify, and it is an old story in fraudulently bankti rupt banks in this community RELIANCE ON SWORN STATEMENTS. Each morning a formal statement was laid before the directors, which falsified the liabilities often by some hundred thousand dollars, yet in their sublime faith in Mr. Riddle, they would not make a five-minute examination of the individual ledger, which would have shown the fulsity of the statements, and at rapid glance would have shown an alarming appearance of overdrafts to doubtful parties. In addition, for some years prior to the failure, Riddle published in most of the Pittsburg papers under oath of the cashier and attested by the names of three direct statements of the assets and liabilities, which were close to a true statement of amounts, and which differed from these weekly statements of several hundred thousand dollars on each side. They also printed and circulated in large 1 numbers cards with the statement thereon as públished in the papers, and those cards were lying around in the bank. en It is practically impossible that any of these directors ho could read did not see the publication in the paper and the cards. The enormous deficiency between these published statements and the weekly statements would seem likely to attract the I