Article Text

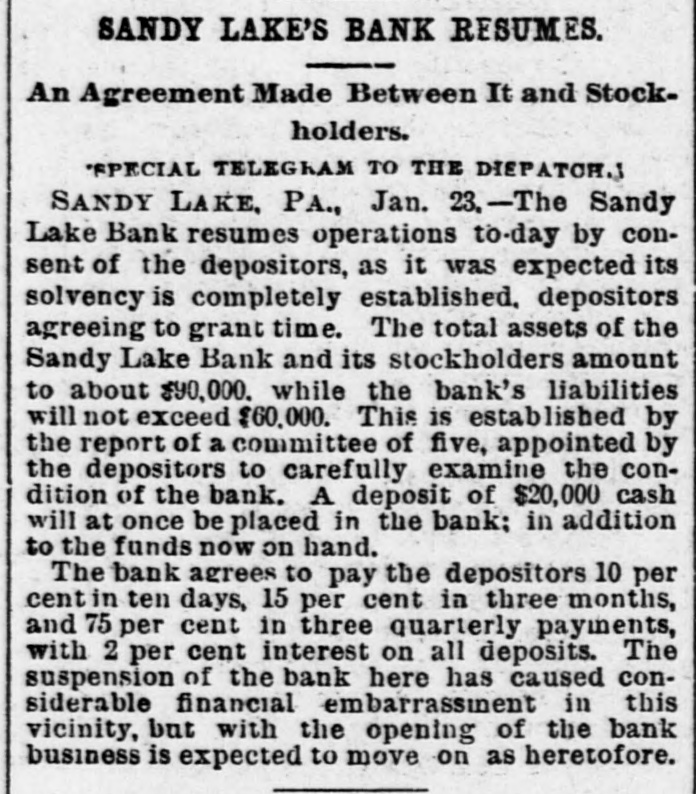

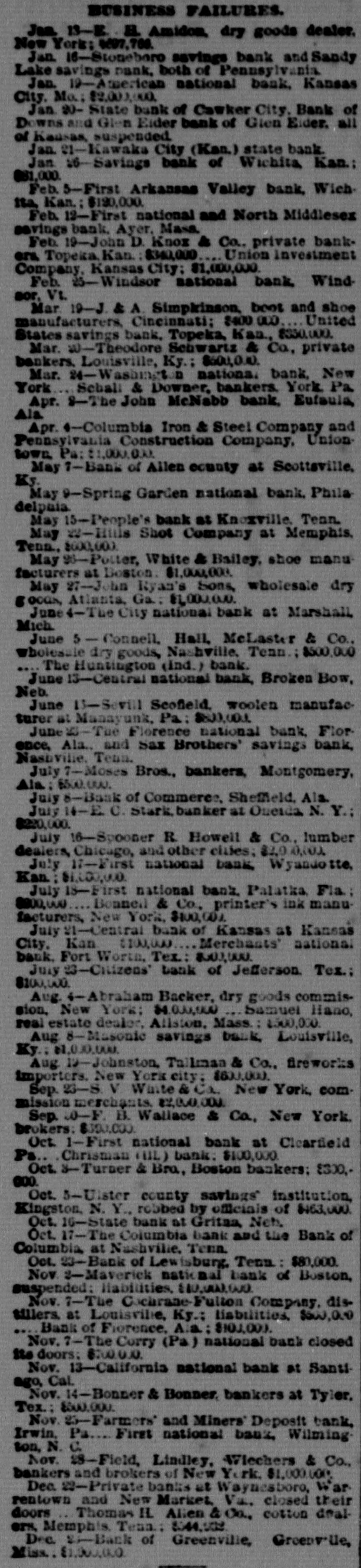

TWO BROKEN BANKS. Causes Which Led to the Assignment of Cashier Zahiniser. ONE BANK THOUHGT TO SOLVENT Tall Tales Told Still by the Nervy Johnstown Flood Frauds. THE PIONEER COKE FUEL FURNACE 'SPECIAL TELEGRAM TO THE DISPATCH.1 SANDY LAKE, PA., Jan. 16.-The assignment of M. L. Zabiniser, proprietor of the Citizens' Bank, of Stonesboro, and cashier of the Sandy Lake Savings Bank, has caused a great excitement in this vicinity. The depositors at once hastened to the bank here to withdraw their money. When the doors were closed some were so much excited as to threaten violence. The doors of the Sandy bank were closed Wednesday evening to avoid a rush by the depositors, who were frightened by the failure of the Citizens' Bank at Stoneboro, one mile distant. Zahiniser has assigned to his son Harry, as trustee, to protect his depositors to the amount of $28,000 and $2,000 and $1,000 to his son Harry. The assets cannot as yet be ascertained. Mr. Zahiniser owns a large interest in a leading drygoods store and considerable real estate, and is also a prominent shareholder in the Excelsior Stock Company of Sandy Lake. The real cause of the failure arises from the fact that R. R. Wright, of Mercer, was contemplating the purchase of an interest in the Sandy Lake Bank, and he would. thereupon. become cashier of the bank. Among the papers upon which Mr. Wright desired better security were those of M. L. Zahiniser. amounting to $18,000. The bank officials urged Mr. Zahiniser to reduce this sum, or otherwise make it good. Fearing an execution Mr. Zahiniser made the assignment to preferred creditors. The Sandy Lake Bank is thought to be entirely solvent, as its stockholders are all men of good financial standing and are individually liable. The deposits in this bank are about $50,000. A reorganization will doubtless be effected soon, a new cashier elected and the doors opened for business as usual. The Stoneboro Bank was opened about two years ago by Mr. Zahiniser as a private institution while yet he remained acting cashier of the Sandy Lake Bank.