Article Text

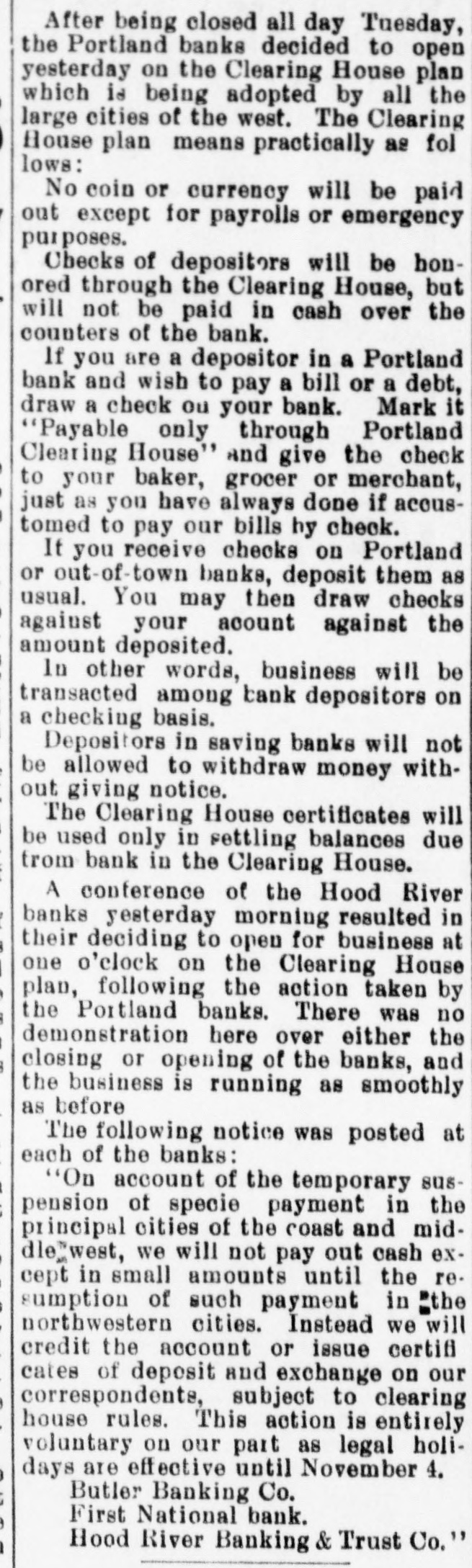

After being closed all day Tuesday, the Portland banks decided to open yesterday on the Clearing House plan which is being adopted by all the large cities of the west. The Clearing House plan means practically as fol lows: No coin or currency will be paid out except for payrolls or emergency purposes. Checks of depositors will be honored through the Clearing House, but will not be paid in cash over the counters of the bank. If you are a depositor in a Portland bank and wish to pay a bill or a debt, draw a check ou your bank. Mark it "Payable only through Portland Clearing House" and give the check to your baker, grocer or merchant, just as you have always done if accustomed to pay our bills by check. It you receive checks on Portland or out-of-town banks, deposit them as usual. You may then draw checks against your acount against the amount deposited. In other words, business will be transacted among bank depositors on a checking basis. Depositors in saving banks will not be allowed to withdraw money without giving notice. The Clearing House certificates will be used only in settling balances due from bank in the Clearing House. A conference of the Hood River banks yesterday morning resulted in their deciding to open for business at one o'clock on the Clearing House plan, following the action taken by the Portland banks. There was no demonstration here over either the closing or opening of the banks, and the business is running as smoothly as before The following notice was posted at each of the banks: "On account of the temporary suspension of specie payment in the principal cities of the coast and middle west, we will not pay out cash except in small amounts until the resumption of such payment in "the northwestern cities. Instead we will credit the account or issue certifi cates of deposit and exchange on our correspondents, subject to clearing house rules. This action is entirely voluntary on our part as legal holidays are effective until November 4. Butler Banking Co. First National bank. Hood River Banking & Trust Co. "