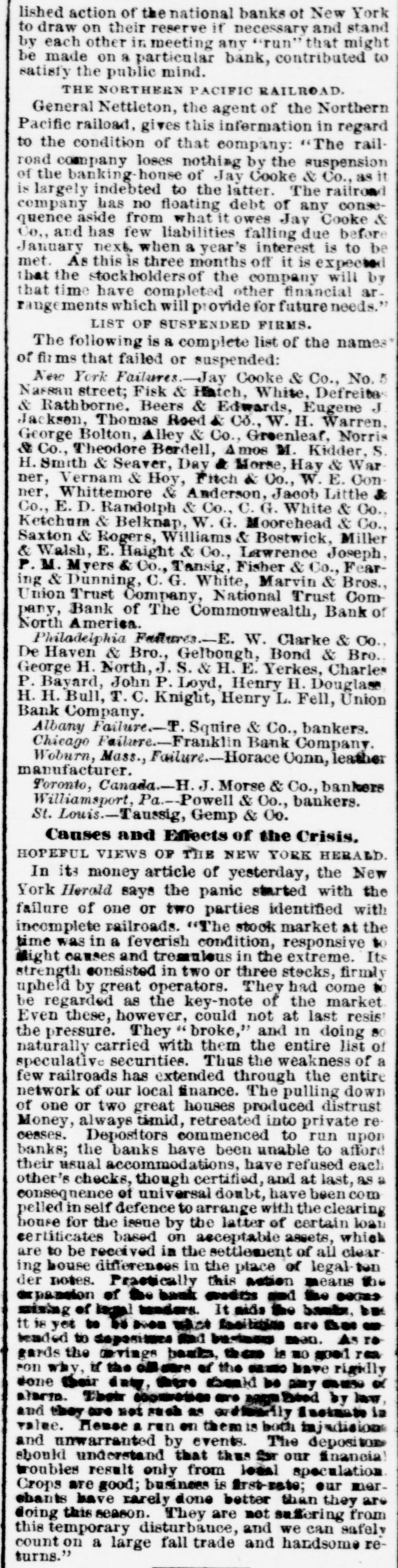

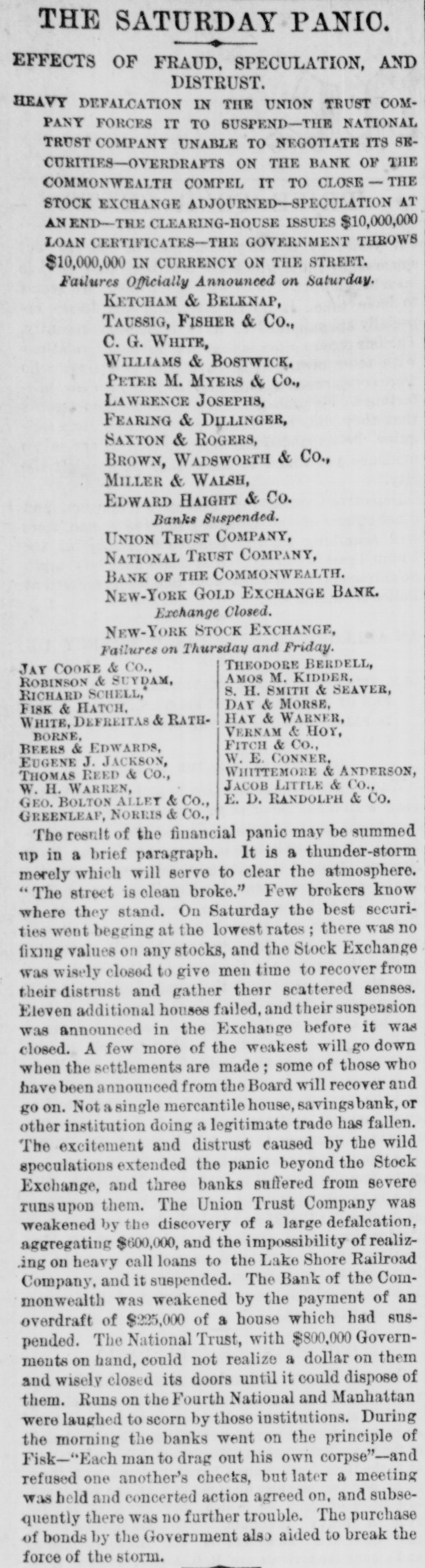

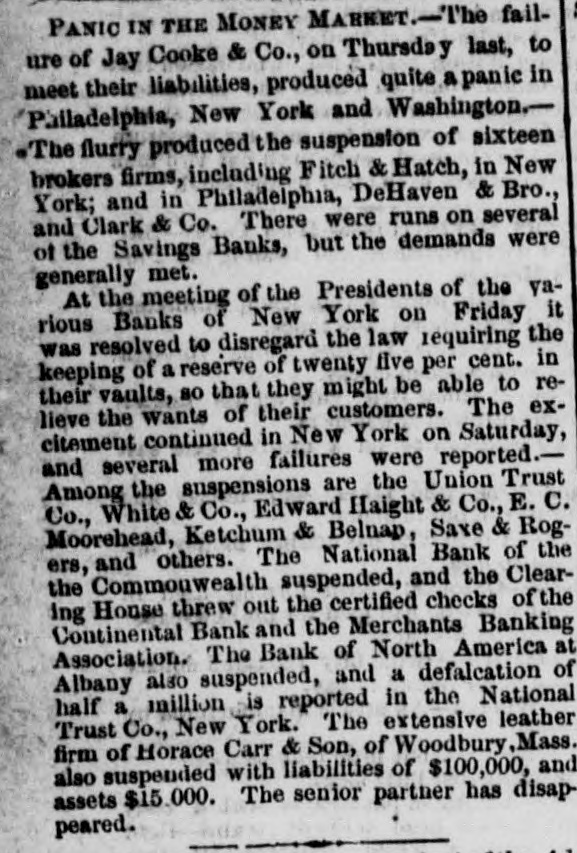

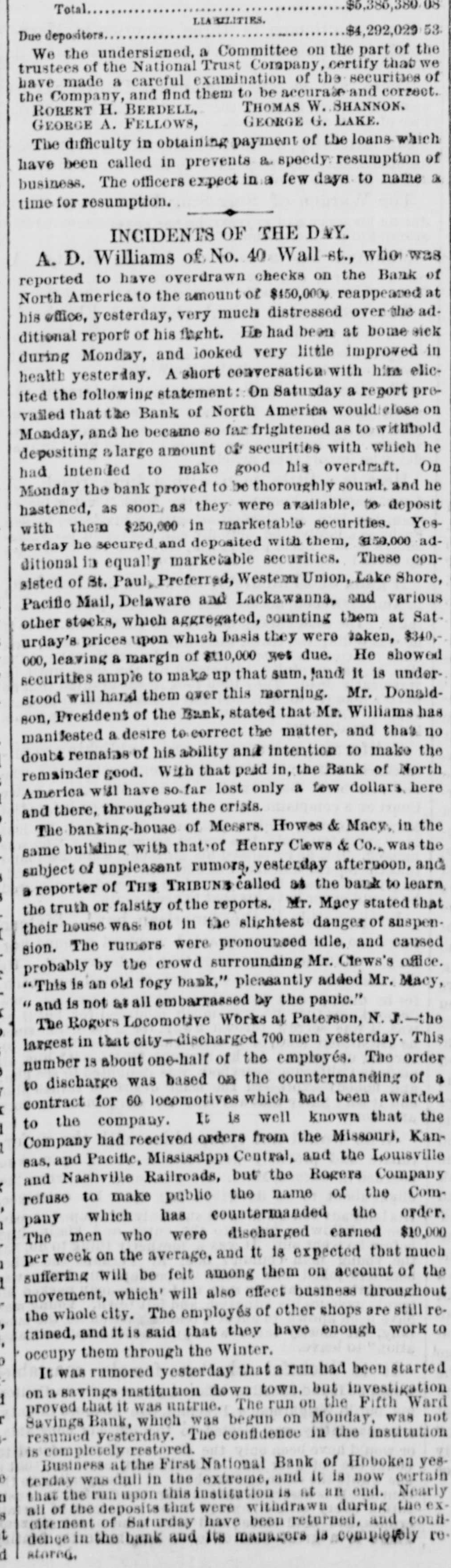

Article Text

THE STATUS OF FISK AND HATCH. NEW YORK, Sept., 29.-The suspension or Fisk & Hatch is said to make probable, theem be resment of the Hoboken bark or savings. A defalcation of nearly $70.00 , was discover in the bank lately and the d'rectors d'spc of some securieties to make up the deficiency, depositing with Fisk & Hatch for keeping $94,000 of the amount realized. The suspension of that firm makes this sum unavailable at present. A REQUEST WRICH COULD NOT BE COMPLIED WITH. NEW YORK, Sept., 20.-A number of telegrams were receiv 1 at the post office yesterday reque: ting the pc +tmaster+1 withhold the delivery of let ers bearing the stamps of the firms. endJay ing sages, and which were addres cod to Cooke Co. The postmaster could not comply with the request as the postal regula Com provide that after a letter has passed from the mailing office the delivery of it can not be pre ven d or delay d by the alleg i writer. A BETTER FEELING IN WALL STREET. NEW YORK, Sept. Bankers and brokers who generally do rot come to business till ten e'clock are again hastening to Wall street. The feeling of olicitude is, however, less than yesterday morning. Confidence prevails this morning, based on the determination of the banks to stand by each other and Secretary Richard on's order buy ten IN Illion bonds today. A MISTAKE CORRECTED. The report telegraphed here yesterday that the su. pended brokers E. P. R indolph & Co. were binkers of the Pennsylvania Central rail rosi is incorrect. SUSPENSION UNTIL MONDAY. The following notice is posted for the Union Tip Company: "In con. equence of the large amount due the company on call loans not having been paid this morning the company have been obliged to suspend payment nntil Monday morning, at 9'olcck. NEW YORK, Sept., 20. 10:00 a. -The Union Trust company has suspended P-J .nent. They announce that they will r sure evement on Monday. Crowds have been a.o.ind the door since morring. THE STOCK MAPKET opened little better, but went of again. Some failpres are announced. ANOTHER FAILURE. NEW Yo: K, Sept., The failure of S. G. White & Co., is announced. COURT ADJOURNED IN CONSEQUENCE OF THE PANIC. NEW YORK. Sept., 20.-The court of general tessiors was adjourn 1 early yesterday to give the jurors and court officers an orcanity ities. look after their bank accounts and 3CD A. G., NOT B. WHITE. NEW YORK, Sept., 20. A. Waite has failed not S. B. White, as before announce d. The failure of E. C. Brodhead, & Ketchem & Belknapare announeed. STOCKS ARE FEVERISH. Most of the sales are for cash which 'stwo or three cents below the regular transaction Governments very weak; nothing doing. WHAT SECRETARY RICHARDSON WILL DO. New York, Sept. 20, 12.35 special from Wasington says it may be stat don the highest authority that should the order to purchase ten milliors of bonds fail to check the financial excitement, it has been decided on by Secretary Richardson to issue any part of the forty million reserve neceseary to restore confidence. FAILURE IN BOSTON AND DISAPPEARANCE OF THE SENIOR PARTNER. BOSTON, Sept. On Wednesday the firm of Horace Conn & Co., of Woburn, Mass., extensive leather manufacturers, suspended payment. Their liabilities amount $100,0 and it is Smated their assets are $150,0 J. Since the suspension Conn, the senior partner, has disappeared, causing great excitement to his family and friends. Search has been made in all directions for him. MEETING POSTPONED TILL MONDAY. NEW YORK, Sept. 20,11:30 a. --The meeting of Jay Cooke & Co.'s creditors announced ior to-day does not take place until Monday. THE STOCK EXCHANGE CLOSED. NEW YORK, Sept. -The stock exch nge is closed, subject to the call of the president, is enable members to settle accounts, &c. VANDERBILT was closeted with Augustus Schell in the office of the Union Trust company immediately 8 er its suspension. STILL ANOTHER FIRM GONE. NEW YORK, Sept. 20, noon.-Brown, Wais worth & Co. have failed. THE STOCK MARKET DEMORALIZED. NEW YORK, Sept. 20, 12.20.-It is impossible to give any quotations for stocks, as they have been thrown in blocks upon the market to realize whatever they could fetch, as they are sold out under the rule. PRESIDENT CHAPMAN, of the stock exhange, has issued an order forbidding all outside operatins of members under the peralty of expulsion. The exchange will not be convened except on his order. PROPOSALS TO SELL BONDS TO THE GOVERNMENT. There were thirteen proposals to sell bonds to the government at the b-treasury, aggregating $2,672,650, atfrom 109 + 5 112. tis stated by the clearing house that the bank statement will not be ready before 4 o'clock, and possibly not then. THE NATIONAL TRUST COMPANY GONE NEW YORK, Sept. 20.-12.45p.m.-The Na. tional Trust Company have just clc ed their doors. The certifications of the Mechanics Banking Association and Continental Bank have just been thrown out of the clearing house. WHY THE STOCK EXCHANGE CLOSED. NEW YORK, Sept, 20,12.50 Stock