Click image to open full size in new tab

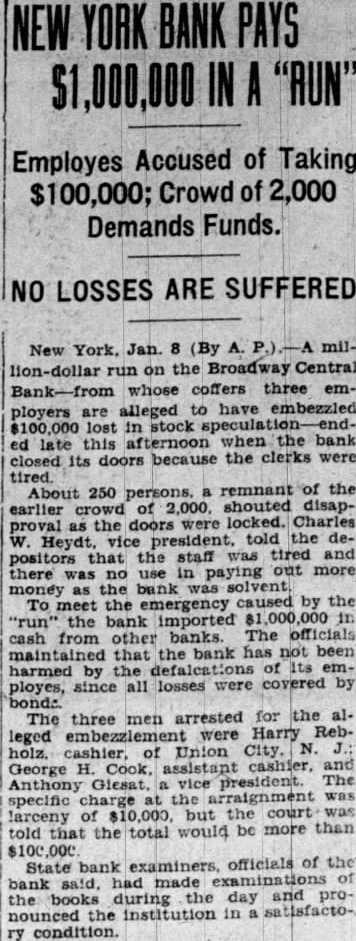

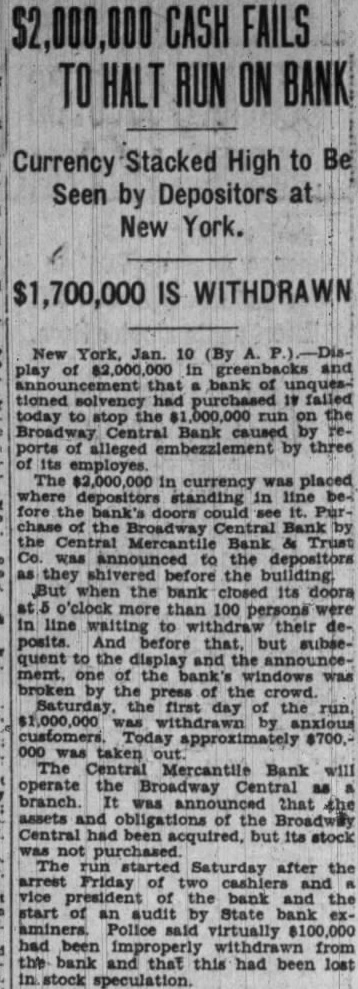

Article Text

DAY IN CONGRESS

Met at noon January 21 and recessed at m. until today at 12 o'clock. appropriation bill. carrying total of $320,020,534 funds for beginning on three reported Senator Maine. in charge bill. urged Senate pointing America far below ratio strength, declaring that military strength can be called economy Spent from o'clock secret of Cyrus Woods. of to be Interstate Commerce Corrimission Democrat) West considered by vote but President ruled vote necessary On appeal from that decision the chair E. Coke Hill San Francisco, nominated division Alaska, Hard States for Bill by Senator Copeland, of New York. designed to repeal Federal for and development of power. Under by Senator Frazier North Dakota, President Coolidge would be directed not to any against Congress in special session that body be not session Senator Norris of braska, introduced resolution calling on foreign to that State into give publicity arouse Mexico. State resolution Senator requested transmit all names dividuals concessions Mexico, names of accepting or rejecting Mexican constitution copies had by department concession Foreign relations committee. 13 to ordered resolution declaring be sense Senate any question involving property rights Mexico proper for Copeland reduce bag limits hunters of game birds, heard distinguished sportsmen and of its all whom game especially are extinction by use highly guns, hunters" of protection

HOUSE. Met at noon 21. and adat 4:35 m. until today at o'clock. Passed deficiency carCharles M. of North

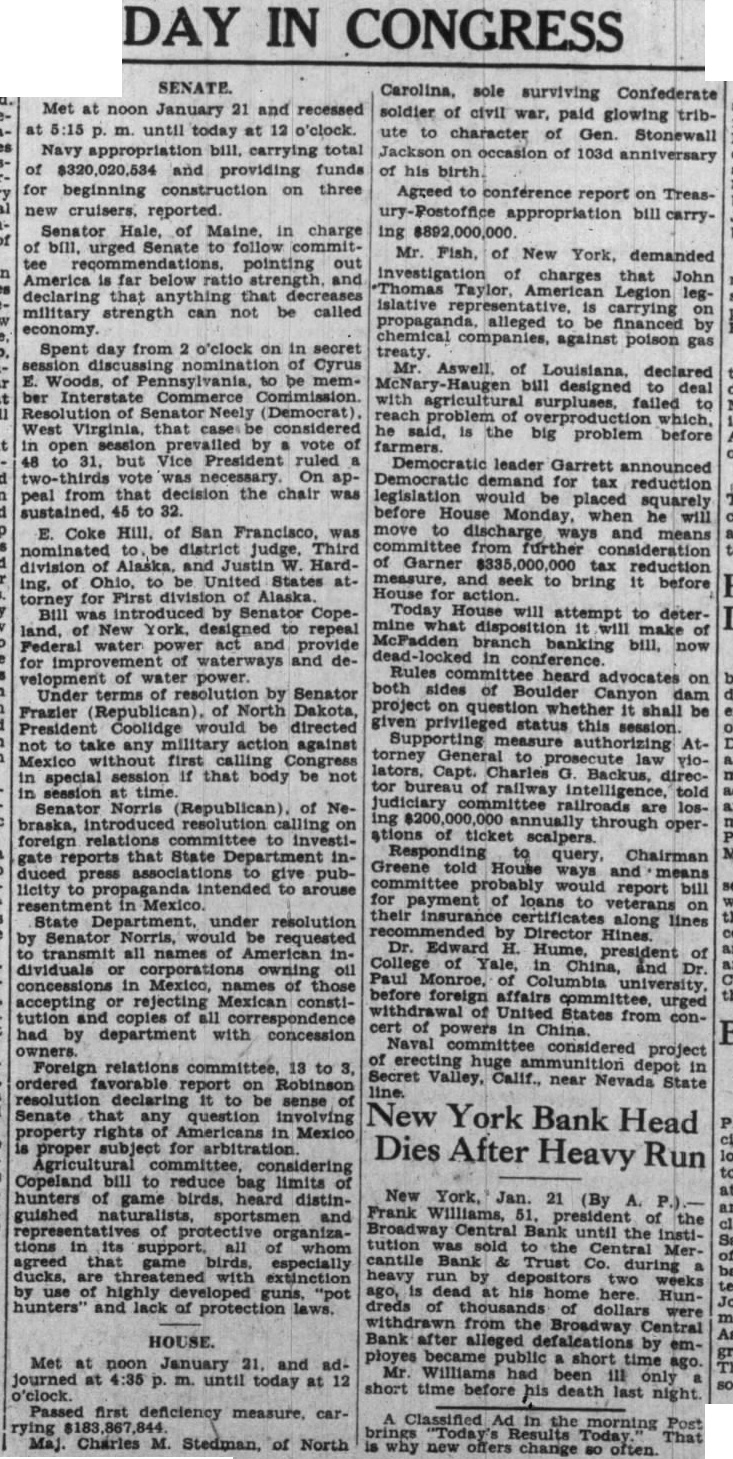

Carolina, sole surviving Confederate soldier of civil war, paid glowing tribute to character of Gen. Stonewall of of his Agreed to conférence Treasappropriation bill carrying Mr. of New York, demanded of charges that John Thomas Taylor, American islative carrying legalleged financed chemical companies, against poison gas Mr Aswell of Louisiana, declared designed to deal with surpluses, failed which, he is the big problem before farmers Democratic leader Garrett announced Democratic demand tax reduction legislation would be placed squarely before House Monday, when he move to discharge and ways means Garner reduction House for to bring it before Today House will attempt to deterMcFadden disposition branch banking Rules heard advocates sides of Boulder project on whether be status this session. Atto law lators, Capt. Charles Backus, bureau of railway intelligence, railroads are ing of annually through operscalpers. Responding Chairman Greene told committee would report bill for payment of loans to veterans along Director Hines. Dr. Edward Hume, Yale, China, Dr Paul Monroe, before foreign affairs United States from of in China project Secret erecting in Valley, near Nevada New York Bank Head Dies After Heavy Run

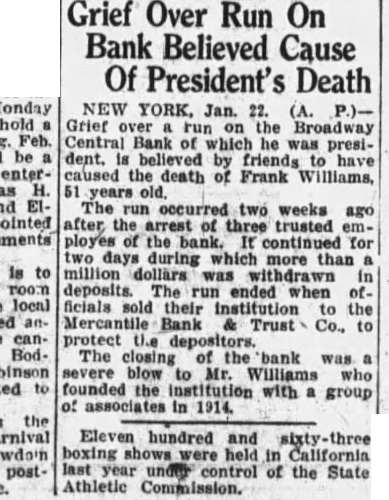

New Jan. 21 (By Frank Williams, tution until the the sold heavy run dead at Hunthe Central Bank after became ago. Mr Williams had short time before his death last night. morning Post That why new offers change so often